Predicting the future has been easy in hindsight. We’re very closely following the script left by Japan, although in fast forward. So we had hindsight right in front of our noses, in a way.

The Western world’s tech bubble, housing bubble, bank crisis, meandering stockmarket, low GDP growth with low unemployment, negative real interest rates, lack of inflation, government policies, central bank policies – just about everything is turning Japanese.

Their economy’s struggle began in the 90s. But we’re catching up fast. These days we’re close behind.

If the similarities continue to hold, then looking at Japan today should tell you a lot about your future. And that will tell you how to invest successfully.

Following in Japanese footsteps

Perhaps the most powerful lesson you can learn from Japan is why the famous Widowmaker trade is called the Widowmaker.

Japan’s government is in an impossible financial situation. Its debts are at 250% of GDP. Which is a meaningless statistic. Japan’s government doesn’t have a claim on the country’s GDP. Tax revenue is only a small portion of that GDP. So let’s do the maths properly.

Japanese government revenue was 55 trillion yen while debt is over a quadrillion yen, costing almost 13 trillion yen in interest per year according to the Japan Debt Clock. That means tax revenue is 5.5% of total debt and interest uses up 24% of total government revenue. This at nigh 0% rates too.

Despite the dire situation, Japanese government bonds are holding up incredibly well. So many whizz kids have bet against the bonds and retired either themselves or their bet since nobody takes much notice anymore. The Widowmaker trade’s victims are some of the most successful investors in the world.

It’s not just the government that’s loaded up on debt though

Japanese companies are borrowing like mad too. They borrowed a record amount so far this year, with huge amounts of bonds issued internationally.

The debt boom is a surprise because Japanese companies historically got their funding in the same way as German companies like to – banks. But this time the companies are using bonds issued overseas. It’s a whole new market that lets the spent Japanese banking system have a rest.

The Japanese version of banking had a key similarity to what made European and American banks blow up in 2008. Academics call it risk and information asymmetry. In the Western world, dodgy loans were repackaged well enough for the eventual investor to lose sight of their dodgy nature. The person taking on the risk of the loans wasn’t in a position to know how risky they are.

In Japan, banks were set up by large corporations to finance those corporations’ investments. That’s why you have the Mitsubishi Bank, for example. This style of banking, known as keiretsu, ended up with the bank as a sort of holding company of the conglomerate. But the point is the same – the bank wasn’t lending for the simple motivation of the profit motive, but for other aims – to finance the conglomerate. This led to the mispricing of risk – too much debt at too low interest rates.

Just as in the West, an entire generation of the smartest Japanese wanted to become bankers. There was even a popular TV show about a career banker and his trials and tribulations. Yes, a popular TV drama about a corporate banker. The show made the phrase “double payback” a part of the Japanese vocabulary. It also redefines the term “melodramatic”.

When your best and brightest want to become bankers, you have a problem. Bankers are facilitators of other people’s endeavours. They don’t generate economic growth or innovate productively.

All this amounts to one thing – a debt bubble. Which leads to stage two – the one the Western world is entering.

The Bank of Japan owns everything

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has a bit of a keiretsu relationship with the national government. In 2013 the governor was replaced for not easing monetary policy enough to achieve the prime minister’s economic goals. Today we have the government’s advisers criticising the new governor for the same failings.

On the other side of the camp we have the head of the Japanese stockmarket who is complaining the BoJ is doing too much. They’re buying so many exchange-traded funds – US$54 billion a year – it’s distorting the entire stockmarket. Trading volume has fallen because of a lack of volatility. The head of the Japanese Bankers Association said he is also concerned about the problem.

In Japanese culture, this sort of criticism at the top is very much out of order. It interferes with Wa – a concept of harmony and cooperation which is very important to the Japanese. Which begs the question why on earth we’re sending Boris Johnson of all people to Japan to try and encourage Nissan and Toyota to invest in the UK. The last time he went, he flattened a Japanese ten-year-old in a game of street rugby.

Johnson may not be the only thing unleashed on Japan imminently. The trigger for a change in BoJ policy may have gone off. The two BoJ board members who opposed the current governor’s wild policies are set to leave this week. Their replacements, both from the Mitsubishi conglomerate, are less likely to stop Governor Haruhiko Kuroda from increasing his easing programmes.

With the government breathing down his neck and his board no longer opposing him, the Japanese central bank might end up owning everything.

Why you should care about Japan

What does Japan tell us about our future?

First of all, John Maynard Keynes’ maxim that markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent certainly holds true for now. Betting on a debt implosion of any government with access to a central bank is a bad idea unless you’ve discovered the secret to eternal life. (European countries don’t have sufficient control of the European Central Bank to make their demise a bad bet, but even there you’ll be waiting a long time thanks to the International Monetary Fund’s support.)

Instead, there’s a different trade you can make with Japan as your guide. There will be an enormous and unexpected reversal in monetary policy over coming years.

The BoJ is the only major central bank not on a tightening path. All other central banks are expecting to raise rates or at least reduce their easing measures.

If history holds true and we continue to mimic Japan, that means central bankers in the West will never genuinely get to tightening policy. Inflation will be too weak, the economy and government financing too reliant on low rates, the stockmarket too addicted to central bank buying, and central bankers too timid to actually tighten.

That’s a profound difference to what markets are pricing in at the moment. If expectations reverse and people think central banks in the West will abandon their tightening, it would move markets dramatically.

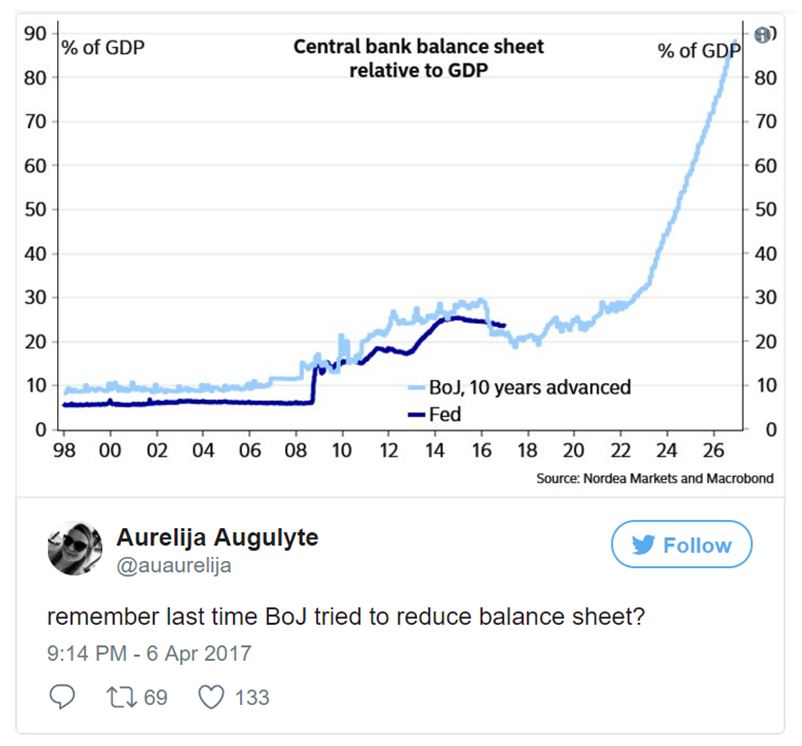

One Twitter commentator illustrated the issue cleverly

In a chart she compared the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet today to the Japanese one ten years ago. Back then the BoJ tried to tighten policy… for a while. Since then it’s been quantitative easing all the way.

If central bankers follow the Japan script once more, they will return to stimulus indefinitely. Gold, stocks and bonds should soar, the yen will strengthen (as other countries move to match Japanese devaluation policies unexpectedly) and financial markets will be safe from a significant crash.

But it’s not all good news. Japan has hardly been an investor’s heaven. You’d be significantly better off spending your funds on Japanese food than the Japanese stockmarket.

One big caveat to all this is whether the world can afford so much of itself turning Japanese at the same time.

With record levels of private debt, Britain is among the worst-off nations if the world turns Japanese. In fact, things are so bad my friends at London Investment Alert are issuing a dire warning you need to see to believe.

If the highly experienced investor Tim Price is right, Britain’s Widowmaker trade will look very different to Japan’s. Watch your inbox for more on this soon.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Central Banks