“After Brexit and this election, everything is now possible. A world is collapsing before our eyes.”

That was the view of Gérard Araud, the French ambassador to the US, on Twitter following the results of the election earlier in the week.

I know, I know. You’re probably sick of hearing about Trump already. But that’s not what I want to talk to you about. Today I want to make a prediction: that by understanding the forces – the powerful, deep economic forces that few people even see – you can predict the next ten, 20 or even 50 years of economic change in advance.

I would argue these forces are completely misunderstood by the establishment. Take the view of Araud above. To me that comment sounds like someone who sees the election of Trump as the trigger for a world “collapsing”.

I think that confuses cause and effect. Actually, it confuses the time lag between the two: it assumes that this has happened all of a sudden, like a building suddenly becoming unstable and collapsing.

In reality, I would suggest it’s been coming a long time. Like a fissure undermining the foundations of a building over decades, we’re now seeing the effects of trends that have been building in strength for a long time.

Artificial intelligence calls win for Trump

Before I explain what they are – an interesting side note. Trump’s election took most people by surprise. But not everyone. Researchers behind an artificial intelligence (AI) system called MogIA weren’t. The system, which uses 20 million data points from places like Google, YouTube and Twitter, has predicted the last three elections correctly.

It called a Trump win in October. It was right.

Contrast that to the human political experts. My mate Sean Keyes (editor of The Penny Share Letter) published an interesting note on just how wrong the experts were in calling the election. As he put it, there are five respected prediction models:

| The Princeton Election Consortium model, which gave Trump a 0.1% chance of winning.

The New York Times’ Upshot model, which gave Trump a 14% chance. The FiveThirtyEight model, which gave Trump a 34% chance. The Benchmark Politics model, which gave Trump a 15% chance. And the Huffington Post Pollster model, which gave Trump a 1.6% chance. |

They were all miles off. But an AI called it accurately, just as it had called Obama’s victories.

Exactly why that is will have to be a story for another day. But one small theory I’d advance is that the AI is free from the disadvantage of human bias. I doubt it wants a certain outcome, which is certainly untrue of the political establishment. There are times when being cold, calculating and unemotional are an advantage: it helps make better predictions and decisions!

The single most important idea you need to understand

Back to the forces behind Trump’s election and what comes next.

There’s a simple way of explaining this. You may have heard the phrase “the future is here, it’s just not equally distributed”. My idea for you today is a twist on that.

Put simply, it’s that the world is growing more prosperous at a rapid rate but that prosperity is not distributed equally.

That’s true of globalisation. It’s also true of the next major global trend we’ll see – widespread automation, driven by robotics and artificial technology.

What’s often forgotten is that it is technology that made globalisation possible by removing the friction in the global transportation and communication networks – allowing goods, labour and capital to flow easily around the world.

Faster and cheaper transport – trains, planes and cargo ships – made it possible and profitable to make things on one side of the planet and sell them on another. Technology enabled companies to take advantage of cheap labour in Asia and ship goods back to the West and still make a profit.

Global competition

Similarly huge steps forward in communication networks made it easy for information and ideas to flow around the world almost instantly and at very little cost. The financial system grew in lockstep, enabling capital to flow freely from one place to another.

The benefits to the world were obvious. In a globalised world, everyone can compete with everyone else. That competition led to lower prices for goods and food – great for the consumer.

But all those low paid workers that technology allowed to compete on a global stage didn’t just drive the price of goods down. They also drove wages down (not necessarily good for the worker in the West who had to try and compete). Globalisation led to the birth of new industries in some places… and to their death in others.

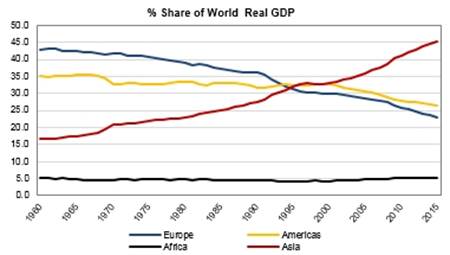

If you don’t believe that I have three charts you need to see. The first is the changing percentage of real world GDP by geographical location. As you’d expect, it shows Asia’s share (red line) doubling during the golden age of globalisation, while Europe’s and America’s share declines.

What that chart shows is Asia – led by China – cashing in on the opportunities created by globalisation. The benefits weren’t evenly distributed across the planet. But there were clear benefits – globalisation made the world a better, more prosperous place, as the following chart shows.

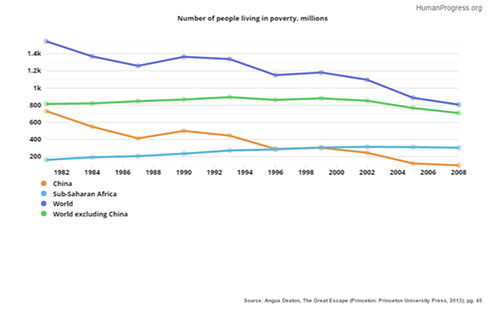

The story here is the same again, told from a different angle. It shows the number of people living in poverty in China in free fall since 1982. Or to put it another way, the prosperity created by globalisation pulled more than 400,000 Chinese people out of poverty.

But if you want to see the whole story told in just one chart, take a look at the below. It shows the growth in household income worldwide. What it shows is that the vast majority of the planet saw huge growth in earnings between 1988 and 2008 – with two exceptions: the very poorest, and those in the 80%-90% percentile, which just happens to be the working and middle class of the West. Take a look:

I’ll say it again because it’s important: globalisation made the world more prosperous… but that prosperity was not equally distributed.

That can have a profoundly dislocating effect on the world. I would argue that “outlier” events like Brexit or the election of Donald Trump are explained by it. People are angry. They haven’t shared in the benefits of globalisation. In fact, they feel like causalities of it. And they’re looking for answers.

A prediction for the next 50 years

That’s important. Because where the key trend of the last century was globalisation, which technology made possible, today technology is starting to change the world in a new way. Instead of making it possible for one nation’s workers to compete with another’s, now technology enables us to simply automate or replace them.

This is already happening. And it’s not necessarily benefiting the people who benefited from globalisation.

Earlier in the year, 60,000 factory workers in China were laid off in a single day… to be replaced by robots. These workers were part of the supply chain for two of the world’s richest firms, Apple and Samsung.

It wasn’t financial pressure that caused the problem. It was technology.

Following a £430 million investment in robotic technology, Foxconn Technology Group confirmed it was cutting its workforce from 110,000 to 50,000. As the firm put it:

We are applying robotics engineering and other innovative manufacturing technologies to replace repetitive tasks previously done by employees, and through training, also enable our employees to focus on higher value-added elements in the manufacturing process, such as research and development, process control and quality control.

Those workers are a symbol of the new forces at work. Globalisation changed the world and in doing so, brought about huge changes to the political landscape. But the most important trend now is towards automation.

And I’d say you need to understand how that’s going to affect your life, wealth and family.

Because really those changes are the tip of a very large iceberg. We’re at the start of a major shift in the world economy, as the forces of globalisation wane and those of automation – predominantly robotics and AI – gather strength.

It will change things, just as globalisation did. And similarly, the benefits of this next technological revolution will not be evenly distributed. For instance, a recent Council of Economic Advisers report claimed that 83% of jobs paying less than $20 an hour could be automated.

83%!

If it’s accurate, that kind of change would put a major strain on society – perhaps more so than globalisation ever did.

It’s not just robotic automation of manual tasks, either. The next five years will likely see increasing numbers of “white collar” jobs replaced by machines. Anything that’s classified as “cognitive routine” – ie, repetitive mental tasks like filling databases or researching large amounts of data – is under threat.

And it’s not just low paid work. I went for a drink with a former city fund manager and a friend looking for work in the city, earlier in the year. The idea was that the fund manager could provide a bit of career advice.

His key point? “Ask yourself: could a computer do that? If the answer is yes, don’t go into it.” Financial services, healthcare, education, law – legal firms already use automated algorithms to plough through past cases – they’re all ripe to be disrupted by technology.

That’s not to say technology won’t make the world a better, richer place. It will. But it won’t necessarily be utopian. The wealth created will likely be concentrated in a fairly small number of places. The people that truly understand what’s happening and invest accordingly will succeed.

For instance, right now capital is flooding towards the robotics industry. Venture capital funding in robotics is growing at a rapid rate, according to author Alec Ross. It more than doubled in the three years between 2011 and 2014. If the Boston Consulting Group is to be believed, the trend is going to accelerate as the industry scales up. The market for consumer robots could hit $390 billon by 2017, and the market for industrial robots could reach $40 billion by 2020.

We’re arguably still at the very start of the trend. But it’s already clear that a major global change is under way, money is moving towards the industries likely to benefit most. That means opportunity.

That’s where our research comes in. It’s the key underlying reason I launched Frontier Tech Investor earlier in the year.

In a world of sweeping, dislocating change driven by technology, you can either hope that your industry is a beneficiary, or you can actively invest in the companies driving that change. If your strategy is to hope for the best, I can’t help you. If you want to be active and try to secure your share of the wealth changes like this create – I’d recommend you take a trial of Frontier Tech Investor.

On that front I have good news. I’m about to publish my first book, called The Exponentialist, which explains all of these ideas and more. It’ll be free for Frontier Tech Investor readers. Look out for how to take advantage of that deal next week.

In the meantime, you can reach me at [email protected]. Perhaps you agree with me. Or maybe you think I’m wrong. Either way, let me know what you think.

Until next time,

Nick O’Connor

Associate Publisher, Capital & Conflict

PS If 83% of low paid workers’ jobs are under threat from automation… which industries are going to grow? Well, according to research published by Goldman Sachs it is “adaptive occupations” that will prosper most. Top of the list were physical therapy assistants (jobs expected to grow by 41% in the next ten years), home health aides (38%) and nurse practitioners (35%). Perhaps that tells us more about the demographics of society than technology. But the two ideas are linked. More on that next time.

Category: Geopolitics