Alright, we’re going to ignore the hullabaloo about the Federal Reserve’s pending interest rate announcement today and concentrate on something far more important: the decay in the international investment position (IIP) of the UK.

Wait! Don’t go. There is something at stake here for you as an investor. What is it?

A reader wrote in last week accusing us of scaremongering. He said all we focused on was gross and net levels of public and private debt. We were leaving out the financial performance of the UK. And in the absence of data showing the financial performance of the UK, we must be shilling to sell subscriptions.

The question about the financial performance of the UK is fair. Taking on debt is one thing. But if you get good value for your money—if the asset you buy generates an income over and above the interest you pay on the debt—well then, everything is fine, right?

Maybe it is and maybe it isn’t. You’ll see shortly. I’m always a little hesitant to go into the details (the proof) of an argument because people’s eyes tend to glaze over when you show them what the country’s international investment position it is.

But I suppose if you’re going to take our argument seriously, you have to be convinced that we’ve looked at all the data, not just presented the facts that support the conclusions we wanted to make in the first place. I can assure you, we’ve been thorough. But let me show you.

First, we’ll look at the current account balance. This partly measures the trade deficit. And that is a function of whether the country is producing or consuming more. Then, we’ll look at the total ownership of UK assets by foreigners and the ownership of foreign assets by UK investors. I’ll ask you why UK investments abroad have been performing so poorly. Finally, we’ll bring it on home.

Regarding the current account deficit (of which the balance of trade is one element) it’s pretty simple. When a country consumes more than it produces, it tends to run a current account deficit. A big part of that is a trade deficit. You spend money on imports. What you spend exceeds the value of your exports.

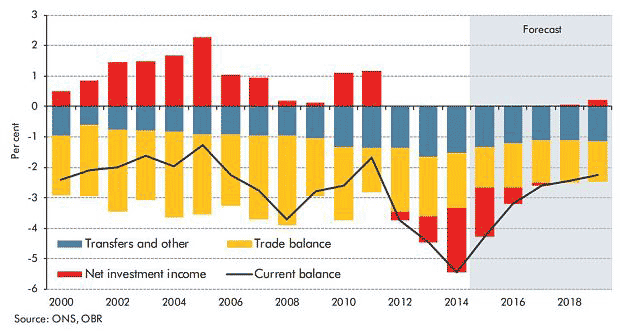

The normal economic penalty for such behaviour is a weaker currency. When markets work, the currency reflects (among other things) whether an economy is saving and investing, or whether it’s borrowing and spending. Britain has been borrowing and spending, the result of which is below.

Source: Office for National Statistics

The chart tells the story. The trade balance is negative. We call that a trade deficit. As a result, the UK’s current account deficit, as a percentage of GDP, hit 6.4% in 2014. It’s improved somewhat since then. Why does this matter?

If you remember when the UK had to go cap in hand to the International Monetary Fund in 1976, or if you remember the crash in sterling after the Tory government had to withdraw from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992, you’ll know that sooner or later a currency always reflects economic fundamentals.

In the current case, a larger current account deficit is a warning sign. It’s one most Britons are ignoring. And at a superficial level, it would be easy to concentrate on the trade deficit and talk about the need for higher savings rates, a lower pound, and an effort to boost British exports.

All of those are good topics. We should talk about them. But they are beyond the scope of today’s Capital and Conflict. The red bar on the chart is equally important.

The red bar shows the decline in Britain’s net investment income in recent years. It also rather optimistically predicts a big improvement. Not so fast ONS!

When you earn more on your investments abroad than you must pay to people who invest in your companies, you have positive net investment income. But when you pay international investors more income than you earn on your investments, you have a deficit.

Again, it’s not that complicated. Foreigners have bought up lots of British assets, including privatised infrastructure. The government banks the cash from the privatisation and uses it to make the government’s own structural deficit smaller. But the income from those British assets now goes abroad.

Yes, there are a lot of variables to consider. But my basic claim is this: Britain’s current account deficit is an economic Achilles heel. Should global investors choose to punish Britain for it, or just rush into US equities and US rates rise, you have the prospect of a large fall in sterling. What does that mean for you?

Well, a fall in the currency is the natural mechanism for reducing a trade deficit. Imports get more expensive and exports are cheaper. But in quality of life terms, it’s not so clear. How would it affect you in your everyday life?

Imports will definitely get more expensive (higher inflation). But exports only rise if you have goods and services the rest of the world wants to buy at a cheaper price. Does Britain have those goods and services? Inquiring minds what to know!

In the meantime, George Osborne continues his record-breaking pace for selling off Britain’s family silver. Osborne aims to raise £31.8bn this year selling the Royal Mail and the government’s stake in the Royal Bank of Scotland. If he gets his way, he’ll sell off more assets in 12 months than all government asset sales combined since 1993.

Do you think it’s a good idea? I do. Nearly all government privatisations are a good idea. It gets the government out of running businesses the private sector can run more efficiently. Consumers get better services and lower prices. That was the theory which led former Chancellor Nigel Lawson to sell off £73bn in public assets between 1983 and 1989.

That reform made Britain a much more attractive place for global capital to invest in. Today, though, the asset sales (which should be argued on their individual merits) won’t generate a huge influx of capital to the country. Instead, they’ll simply transfer the income from those assets to mostly foreigners. And they’ll be a short-term plug to a long-term government budget problem.

Have a look at the comments and the charts from recent data published by the Office for National Statistics. And let us, because they paint a gloomy picture, take the statistics at face value. First an explanation, then some pictures [emphasis added is mine]:

“The current account deficit widened in Q3 2014, to 6.0% of nominal Gross Domestic Product GDP, representing the joint largest deficit since Office for National Statistics (ONS) records began in 1955.

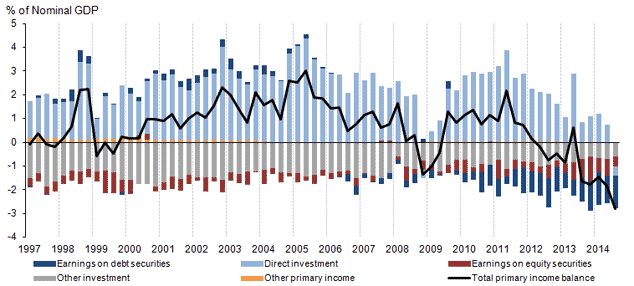

“This deterioration in performance can be partly attributed to the recent weakness in the primary income balance, which captures income flows into and out of the UK economy. This also reached a record deficit in the Q3 2014 of 2.8% of nominal GDP; a figure that can be primarily attributed to a fall in UK residents’ earnings from investment abroad, and broadly stable foreign resident earnings on their investments in the UK.”

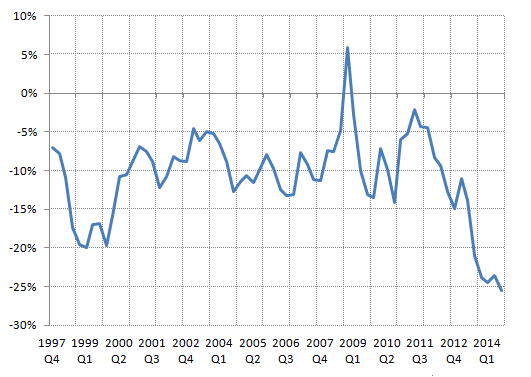

With UK residents investing in overseas assets at a slower rate compared to their foreign counterparts, there has also been a worsening of the international investment position (IIP). The UK’s IIP comprises of UK assets (UK residents’ holdings of overseas assets), and UK liabilities (foreign owned assets in the UK); with the Net International Investment Position (NIIP) simply the difference between them.

It broadly represents the accumulated deficits that the UK has run with the rest of the world and gives an indication of the degree of external balance that the UK experiences.

Since 1985, the UK’s NIIP has been on a downward trend. During the economic downturn, it briefly turned positive, reaching £88.9bn (around 5.9% annual GDP), but has declined since and remained negative for 5 consecutive years, dropping to -£450.7bn in Q3 2014 (around 25.5% of annual GDP).

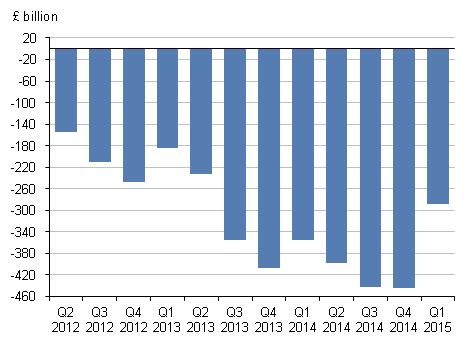

Now the charts. They show that the UK has been earning less on its foreign investments, that our total external liabilities are nearly £300bn, and our net international investment position, as a percentage of GDP, is worse now than at any time in the last 20 years.

The primary income deficit grows

Source: Office for National Statistics

UK net external liabilities of £293bn in 2015

Source: Office for National Statistics

Net international investment position as a percentage of GDP

Source: Office for National Statistics

If you don’t want to take my word for it, here is John Longworth of the British Chambers of Commerce on what’s at stake for Britain and for you [emphasis added is mine]:

“The current account deficit is as big of a risk to the UK’s future prosperity as the eurozone crisis or other international shocks – and it is high time this stark fact is recognised.

“Although businesspeople and the Bank of England keenly understand the risk that an unsustainable current account deficit presents, successive governments have failed to treat it with the seriousness it deserves. The size and persistence of the UK’s current account deficit make us hugely vulnerable to external shocks, unexpected shifts in market sentiment, and unwelcome downgrades to our credit rating.

“While it is good to see some improvement over the quarter, the huge current account deficit should be setting off alarm bells. Recent improvements mask long-term falls in net investment and overseas income, as well as our lacklustre export performance. These issues merit immediate and sustained attention, both in Westminster and in boardrooms across Britain.”

Good luck getting Westminster’s attention. Or boardrooms. But at least you can be alert yourself.

Category: Economics