They say our love won’t pay the rent

Before it’s earned, our money’s all been spent

I guess that’s so, we don’t have a pot

But at least I’m sure of all the things we got

Sonny and Cher, I got you, babe

If you’re not familiar with Bill Murray’s 1993 classic film Groundhog Day, do yourself a favour this week and watch it. It will help you understand what’s going on in Greece. The task of today’s Money Morning is to reconcile the Greek election result with the Fed’s fiddling last week, and show you what it all means for your money (which is increasingly under attack from authorities at the Bank of England).

The film, by the way, is one of Bill Murray’s finest performances. He plays Phil Connors, a condescending weatherman from Pittsburgh, who is forced to relive the same day until he gets his moral house in order. Conners tries a bit of everything—French, gluttony, hedonism, and becoming an expert at Jeopardy—before finding salvation in, you guessed it, love.

As signals go, you could do worse than Groundhog Day. It’s on 2 February. It’s the day when an affable rodent emerges/is dragged from his man-made home in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. If he sees his shadow, you get six more weeks of winter. If it’s overcast, spring is in the air.

It’s a contrarian signal to be sure. Sun equals winter while shadow equals spring. But what does any of this have to do with Greece? Is it spring? Is it winter? Or is it the same day over and over again?

Well, the good news is that things in Greece have changed. The bad news is that they also appear to have stayed the same. Alexis Tsipras and his left-wing party Syriza have won Greece’s fifth election in six years. The party didn’t win an outright majority in Greece’s 300-seat parliament. But with 35% of the vote, it outpolled its main rival, New Democracy (28%), and can form a coalition with the nationalist Independent Greeks.

Tsipras now has a mandate. But a mandate for what? His party rose to power in January of this year on a wave of anti-austerity sentiment. Then, behind closed doors, the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank (mostly the Germans) put the screws to Syriza and said no more bailouts without reform.

The Greek voters did the sensible thing in July, when presented with a referendum from their creditors. Over 61% of them told their creditors to get lost. It was a vote to stay in the euro and reject the terms imposed by creditors. To paraphrase former US Treasury Secretary John Connolly, the Greek public told the Germans “it may be our debt but it’s your problem”.’

And here we are, six ballots later, and no closer to a resolution. Or are we? The Greek bailout will be reviewed by the end of the year. At stake is €85bn in future bailout funds. The Greeks have elected a party that has both accepted and rejected austerity.

One way of looking at it is that the Greeks and the ECB will find a way to muddle through. In nominal terms, even if Greece defaulted on all of its €320bn it wouldn’t be the end of the world. Europe would manage.

But the French, the Italians, and the Germans certainly wouldn’t like it, nor would their banking systems. Those three countries own €223bn of Greece’s outstanding debt, or 67%. They own it through their participation in the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF). The EFSF was created in 2010 to clean up sovereign debt crises in Ireland and Portugal.

And now you start to see what’s really at stake. It’s not Greece. It’s the viability of the whole European project. Greece, in fact, might be better leaving the euro, defaulting on its debt, and rescheduling with its creditors. But the authorities in Europe can’t let that happen. Why?

The whole post-World War II project in Europe has been an attempt to keep France and Germany from going to war again. To be fair, it’s worked. ‘Ever closer union’ in Europe, be it political or economic, has made the entire continent interdependent, and thus less likely to resort to armed conflict. That’s progress.

But if Greece leaves, then the European project fails, or at least changes dramatically. Maybe it’s time for a change. Either way, the time is quickly approaching for Britain to decide how much it wants to be involved with Europe. But that question – Britain’s future in Europe – is beyond the scope of today’s Money Morning.

For now, the Greeks have given markets what they least like, more uncertainty. In that respect, the Greek election result confirms what John Stepek said on the MoneyWeek podcast Friday: more QE from ECB and the Bank of Japan, which, John argues, could be bullish for stocks.

A signal from Sydney?

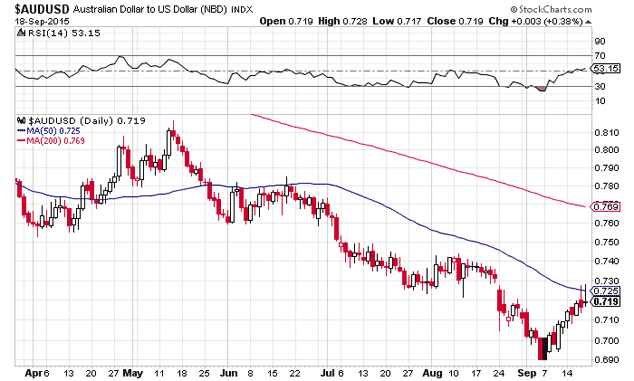

Speaking of signals and stock prices, the Australian dollar has gotten up off the mat against the US dollar. The leadership spill in the Liberal Party has put former Goldman Sachs man Malcolm Turnbull in charge of the country. Turnbull is Australia’s fifth prime minister in eight years, and the second to rise to the post through an internal leadership coup. The Aussie dollar, tired of all the bloodshed, is pleased, as you can see from the chart below.

The currency bounced a good five days before the political change. It’s interesting how prices work as signals when they’re allowed to. On a technical basis, the Aussie was oversold against the US dollar, judging by the Relative Strength Index (RSI). Any time that’s below 30 (the scale above the chart), it suggests a security or index could be oversold.

You’d expect the Aussie to be oversold, given that Australia has been a proxy for growth, China, and commodities. In a low-growth world with a Chinese financial crisis, it’s been a tough summer for Australia. And now?

The overt dovishness of Janet Yellen’s Fed statement last week could see a rally in emerging market currencies and stocks. I say ‘could’ because you never know. Just because the Fed says it won’t raise rates, perhaps not even in 2016, doesn’t mean it won’t. But without higher US short-term rates, there are only so many justifications for a stronger greenback. More on those tomorrow.

Osborne flies to China

China’s president, Xi Jinping, is off to Washington to meet Barack Obama. Obama, by the way, has less than 500 days left in the White House. That should make for some interesting grand strategy between the two countries. They’re engaged in a currency war, yet both depend on the other economically.

Where does Britain fit between the world’s two-largest economies? In a tight spot, I would suggest. But ask the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne. He’s the one who’s flown off to Beijing to drum up Chinese investment in Britain.

As a country with a chronic trade and current account deficit, Britain needs all the foreign capital it can get. For starters, Osborne announced approval of a £2bn investment by the Chinese in the Hinkley Point nuclear power station. French giant EDF has yet to make a final investment decision on the project. The Chinese investment should help.

Britain is already a founding member of China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. That is a direct rival to the US-based World Bank. And more Chinese capital comes to Britain than any other country in Europe, according to official figures reported by the Financial Times.

MoneyWeek’s editor-in-chief, Merryn Somerset-Webb, has been adamant that Chinese financial bubbles shouldn’t discourage investors from looking at the long-term big picture. She reckons that big picture is bullish. One big reason is China’s plan to build a ‘New Silk Road’ from the South China Sea all the way to Rotterdam.

That’s not just a big project. That’s a plan to remake the post-war global economic order. That’s grand strategy done properly. What’s the British response? Stay tuned.

The Bank of England floats cashless trial balloon

Finally, I’m not going to comment on Friday’s speech in Northern Ireland by the Bank of England’s chief economist, Andrew Haldane. Tim Price has already foreseen this move in his new report. If you missed it this weekend, you should watch it now.

Yes, I know it will generate a lot of controversy if you’re the sort of investor who believes the authorities have your best interests at heart. But if you’ve learned anything in the last week, it’s that we’re in the midst of a giant monetary experiment run by people who have a textbook understanding of the economy. How do you think that’s going to end?

There are only a couple of ways in can end. Tim has highlighted one in his report. Andy Haldane wasn’t that subtle in his speech last week. Negative interest rates—where you pay the bank interest on your money, are one of several tools left in the toolkit of central bankers who are increasingly desperate to keep you inside their system.

Here’s what Haldane said last week (emphasis added is mine):

“A more radical proposal still would be to remove the ZLB [zero lower bound] constraint entirely by abolishing paper currency. This, too, has recently had its supporters (for example, Rogoff (2014)). As well as solving the ZLB problem, it has the added advantage of taxing illicit activities undertaken using paper currency, such as drug-dealing, at source. A third option is to set an explicit exchange rate between paper currency and electronic (or bank) money. Having paper currency steadily depreciate relative to digital money effectively generates a negative interest rate on currency, provided electronic money is accepted by the public as the unit of account rather than currency. This again is an old idea (Eisler (1932)), recently revitalised and updated (for example, Kimball (2015)).

“All of these options could, in principle, solve the ZLB problem. In practice, each of them faces a significant behavioural constraint. Government-backed currency is a social convention, certainly as the unit of account and to lesser extent as a medium of exchange. These social conventions are not easily shifted, whether by taxing, switching or abolishing them. That is why, despite its seeming unattractiveness, currency demand has continued to rise faster than money GDP in a number of countries (Fish and Whymark (2015)).

“One interesting solution, then, would be to maintain the principle of a government-backed currency, but have it issued in an electronic rather than paper form. This would preserve the social convention of a state-issued unit of account and medium of exchange, albeit with currency now held in digital rather than physical wallets. But it would allow negative interest rates to be levied on currency easily and speedily, so relaxing the ZLB constraint.”

Category: Economics