Yesterday I introduced you to the 18-year cycle and made a claim that this is the key roadmap for you to have as an investor to build long-term wealth for yourself and your families.

But I know that some of you will be sceptical that the cycle will repeat this time around. This time has to be different, you will argue, because the world is changing so rapidly.

And you’d point to the breath-taking pace of technological innovation. Or maybe the rise of China and the Asian middle classes. Or you might point at problems we have these days – such as a looming trade war (or perhaps worse) between the US and China, or the imminent collapse of the euro, or Brexit, or Trump and so on.

Fair enough, would be my response. These are important issues and have the scope to make massive changes to the world we live in. But I am going to argue that there’s something even more fundamental at play which drives each cycle forward.

It’s a hidden “force” both explains why the cycle must arise and helps me make long-term forecasts.

It’s called the Law of Economic Rent. You may never have heard of it but once you understand it, you’ll see it everywhere. To illustrate my point, let’s begin our story in Davos, where in January of each year, the world’s elite gathers in this small Swiss town to discuss the most important trends and issues affecting the global economy.

In snowy Davos…

2019 was the 49th such time they have done this, at the annual event hosted by the World Economic Forum (WEF).

The meetings take place in Davos and Klosters, both charming and beautiful but otherwise unremarkable Swiss towns. But the meetings WEF hosts for this one week in January attracts a large media following, largely because of the stellar cast of attendees who make what (for global capitalists) amounts to an annual pilgrimage.

You have princes and politicians, billionaires and their financiers, conservationists and philanthropists, academics and activists all in one place. You name them and they are likely to be in attendance.

The coverage of topics this year did not disappoint – globalisation, trends in healthcare, environmental conservation, privacy, cybersecurity. All of the important issues are debated and discussed.

These people do not shy away from discussing the big themes. But there’s always an air of self-congratulation about their deliberations: we are doing the right thing just by showing up and having a good chat, they seem to suggest.

Though this year they were openly challenged by one of the attendees, Rutger Bregman, a Dutch historian. He called out the blatant hypocrisy of people flying separately in private jets (used by many of the attendees) to discuss environmental protection. Or the fact that billionaires seemed very keen to discuss how to alleviate the problems of poverty, hunger and deprivation (which are still all too common in the world) but refused to discuss tax avoidance which would provide revenues to countries to make the necessary investments to help prevent such problems arising in the first place.

But nowhere in this or any of the other 48 prior WEF meetings did any of the participants discuss the fundamental cause that leads to the heart of many, if not all, of the problems they seemed to be discussing. Despite the impressive array of political, economic, financial and intellectual talents on display in Davos none of them, not a single one, engaged with the most important aspect of all of this.

This is the hidden cause and it’s called the Law of Economic Rent.

It explains the seemingly irreconcilable features of our system: unending progress that is nevertheless interrupted by periods of soul-crushing stagnation. But it also explains that though free markets (unlike other systems of human organisation) are the vehicle for realising such enormous prosperity most people get left further and further behind. Or why politics – in all countries – come to be dominated by land and banking interests, even more so than the interests of other businesses and certainly individual citizens. Why countries with the most abundant resources seem to have the most internal strife. Or why the great powers seem incapable, in the final reckoning, of peaceful co-existence.

We accept all of these features as just the way that things are.

They do not have to be. But to make changes you have to understand the cause.

When is it ever possible to earn a year’s income in just one week?

The real news does not always make the biggest splash. And so it is in Davos. Despite the enormous media attention the event garners, the real story was not who said what at the meetings but what in fact happens before they even begin.

Here’s how the Financial Times (FT) described the usual annual “chaos” in the two towns as the global elite came visiting this year:

The arrival of bus loads – and the odd helicopter full – of the global elite, has a profound effect on the town. “Everybody knows this is the time of year when everything changes”, says Dagmar Weber, Director of Residences at the Hard Rock Hotel, Davos. It is, says Weber, “regulated chaos”, but she estimates more than 90 to 95% of the locals profit from this type of meeting. They work with it.

95% of the locals may profit – but that depends on whom you count and how they profit. Some do so far more than others. The biggest profit is seen in the apartment rental market. The proof is in the numbers:

- The average nightly rental during Davos is a shade under £2,500 per listing, the FT reporters found on Airbnb.

- Three nights for a double room at the nearest hotel would set you back around €7,484. For the same length of time the week after the WEF meetings, the cost drops 97% to €237.

So, some hotels could be expected to earn during that one week of the WEF meetings the same as they would likely earn for the entire rest of the year.

So far so good. Space is limited, demand surges and so prices rise in response.

But would the same thing happen for the bartender serving the elite their pre-supper cocktails in the evenings?

What do you think?

Could said bartender – or cleaner, receptionist, bellhop, waiter or any hotel staff for that matter – earn during that week the equivalent of a year’s wages? Have you heard of that happening anywhere, in any job, you have ever worked in – no matter how much your services were in demand?

I seriously doubt it.

It’s clear once you think about it. The person who has the right to charge the rent takes most, if not the entire, amount of profit in the end.

If workers in Davos started to demand significantly more money while the WEF was taking place, the owners of businesses would simply find new workers. Similarly, if suppliers of hospitality and other services decided to increase their prices by almost any amount (let alone the 30 or 50 times increase that property or hotel owners were able to earn), the event organisers would simply take their business elsewhere.

New people and businesses would be happy to come in if there were a gap. This is healthy competition and keeps a lid on prices.

But this mechanism does not work with respect to location, which is what we are talking about when people are trying to find a room to stay in while attending the events. The available sites in that location are limited in number. So you have to pay effectively whatever is demanded. The only limit ultimately is what people are capable of paying.

And in an event attended by billionaires, that can be very high indeed.

This is the Law of Economic Rent in action. And it’s key to understanding what goes on in our economies.

Does economics have “laws”?

People, including many natural scientists, tend to dismiss the idea of there being any “laws” in social science disciplines such as economics. This is because human relationships and interactions seem to be too messy and subjective and what might be true in one case may not be true somewhere else.

I can see their point, even though I disagree with it. We don’t see these laws because we are using flawed models.

However, if a scientific law is (according RealClearScience.com)

… a statement based on repeated experimental observations that describes some aspect of the world. A scientific law always applies under the same conditions, and implies that there is a causal relationship involving its elements

… then the Law of Economic Rent is a scientific law indeed. We have all of modern economic experience to prove its existence in all sorts of settings. We even see its operation in “experimental” virtual reality, as I wrote about for my Cycles, Trends and Forecasts readers.

Make no mistake: the Law of Economic Rent is a cast iron economic law. It is to economics what the law of gravity is to physics – the very foundation of the discipline.

Of labour and capital… and land

Let’s take a step back for a second and go back to first principles.

Our understanding of the Law of Economic Rent was shaped most of all by David Ricardo in his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation published in 1817 and by Henry George (who was heavily influenced by Ricardo) in Progress and Poverty published in 1879.

Ultimately, economic activity is about generating wealth. Wealth was defined by George as a material product produced by labour (ie, human beings interacting with one another to make things) to satisfy human wants and desires.

To create wealth you need three factors of production: labour – ie, people to work; and some capital – ie, equipment.

Over time, our labour has got far more sophisticated as we have developed skills and our capital equipment has gone from, say, a simple hammer to highly advanced computing technology.

But you also need some land.

Land includes the physical earth we think of land as well as anything freely supplied by nature, such as natural resources.

The economy is simple: when three factors of production interact, wealth is generated. Everything has to take place somewhere – ie, it needs a piece of land. And human beings need to use tools – or in the modern world, machines or computers – to produce the goods and services that people want.

So far so good, I hope.

Each factor of production earns a part of the output that is generated as wealth. Labour earns wages. Capital earns what those economists called interest – but it’s more than interest on a bank loan. Think of it as a return that is needed to induce that piece of equipment to be put to use. And finally land earns rent.

The classical economists were not merely content to describe how things worked. They were interested in knowing how and why the earnings to each factor varied.

Ricardo first noticed that an equal amount of labour applied to a site might result in very different earnings. He was studying agricultural land output.

A fertile piece of land would result in a much larger yield than one in a less favourable location. Fertility is of course linked to location – areas which have abundant water, good sun and are sheltered from wind and inclement weather. A less favourable location might still yield enough produce to earn the person working on it a sufficient living, but a better site would yield enough for that person to earn a living as well as a surplus.

The difference between the product on a better location and the most “marginal” one – ie, the one that yields just enough so that one can just about get by on what comes out of it, is the site’s economic rent.

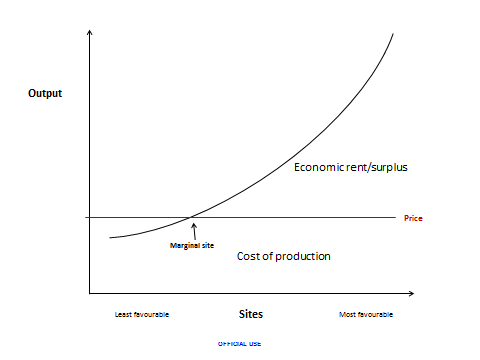

This is depicted in the diagram below.

Source: Ascendant Strategy

Source: Ascendant Strategy

Imagine all locations are lined up in a row from least to most favourable. The output (the black line) is going to be much higher on the best site compared to the worst. Some sites will not be viable because the market price means you can’t generate enough output to cover your costs (where the black output line falls below the red price line). In this formulation the costs of production include wages, capital costs and business profits (other than rental income).

At the marginal site, there’s an incentive to produce because the market price (red line) equals the cost of production (including wages and a reasonable return on capital investment). At all sites that are in a more favourable location to the marginal site, where output is higher, the additional output is a surplus or economic rent.

This is the return that comes about not because of the skill of the person working on it but because of the gift of nature – in this case, fertility of the soil.

The site owner captures the surplus or economic rent.

Now, if you are an owner of the site, you’d be able to pay someone pretty much the same wage to work the land as you would on the marginal site.

Why is that?

Well, for the same reason that the hotel staff in Davos don’t get paid extra during the WEF meetings. Because if the labourers on the fertile site demand more money, there will be others, at more marginal sites, willing to come in and do the job instead. The only time this calculation changes is if there is a shortage of workers – and then wages rise (but for everyone, not just the workers on the best sites). And in any case, this rarely happens, at least over the medium to long term.

The same would be true of, say, the suppliers of tools to farm the land. If they demanded more from the owner of the more favourable site they would not get any business. This is true of anyone else providing capital equipment so that the land can be worked on to produce output.

This means that over all sites being used, wages and returns to capital are fairly similar because of market competition.

But this leaves the residual, or surplus or the economic rent, to go straight to the pocket of the site owner.

In other words, found Ricardo, the more favourable the location, the more the division of wealth got skewed towards the owner of the land.

Rents go up as society progresses

This brings us to Henry George. He had studied the great classical economists and understood what Ricardo was pointing out.

He put it thus:

That as land is necessary to the exertion of labour in the production of wealth, to command the land which is necessary to labour, is to command all the fruits of labour save enough to enable labour to exist.

In other words, land is vital to production, it is fixed and immobile (unlike labour and capital) and therefore it will take the surplus of production. Returns to labour, on the other hand, will be held in check, in some cases only just enough to enable people to eke out an existence but have nothing left over.

(Does this last point reflect what we see going on around us these days, especially in the more marginalised communities in our countries?)

George applied Ricardo’s essential insight on economic rent to urban land. What a day’s work can get you on a plot on the corner of Oxford Street and Regent Street compared to an equivalent amount of effort in, say, a site on the outskirts of Inverness would be enormous. This is because of the favourable location of the former being at the heart of the largest market in the country.

George understood that the scale of rent generated in the industrial economy was far greater than in the largely agricultural economy which Ricardo was more familiar with.

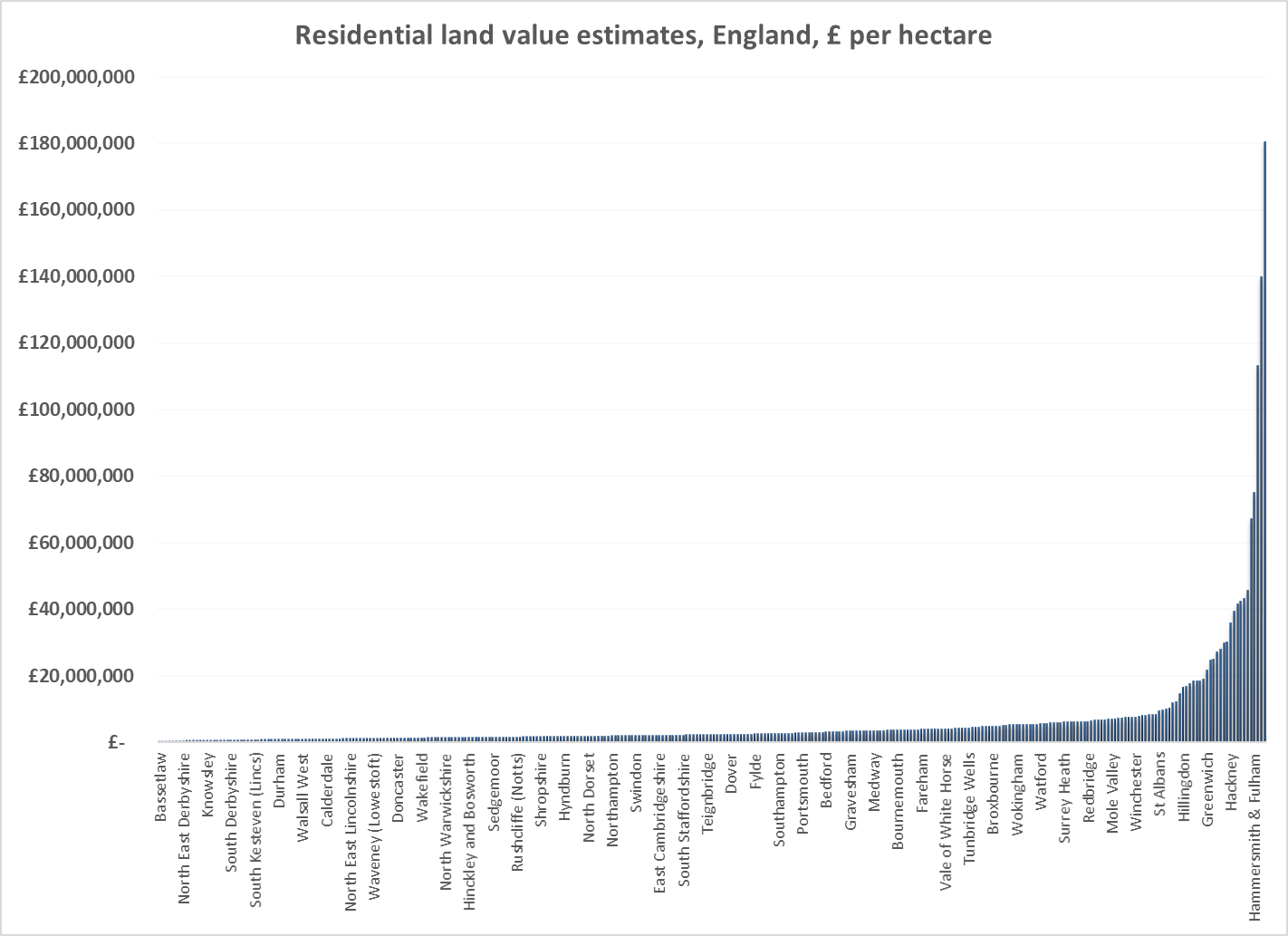

If you want to get a sense of its enormity, take a look at the following diagram.

Source: Office of National Statistics

Source: Office of National Statistics

This diagram plots the estimates of residential land values in England by local authority area. These are not market estimates but econometric ones, based on averages, and are intended to be used for modelling or policy appraisal purposes.

However, the data is revealing. Residential land values – that is the value of land zoned for housing – range from a low of £370,000 per hectare in Bassetlaw in the East Midlands to over £180 million per hectare in the City of London.

Yes, you read that correctly.

The value of residential land at the heart of London is almost 500 times more valuable than the cheapest areas in England.

In fact, the 30 most expensive areas in the country are all in London and only two areas, St Albans in Hertfordshire and Elmbridge in Surrey, have more expensive land than the cheapest local authority area in London (Havering).

The difference in values is pure economic rent. If Bassetlaw is indeed the most marginal location in England, the value of every location outside it will contain an element of it. The closer you get to the centre of London the size of the rent grows exponentially, as you can see from the shape of the curve.

Multiply this up over every site in the country and we are talking about trillions of pounds. In fact, the Office for National Statistics has estimated the total land value of the country at somewhere over £5 trillion.

On the other hand, what someone would earn in wages in Bassetlaw would likely be quite similar to what you would earn for an identical job in London. There may be some variations involved but the will not be of the order of magnitude (500 times) we are talking about with respect to housing land.

But George was also interested in the dynamic picture regarding rent – how it behaves over time.

George understood that as economies progress, the size of this rent get ever greater because what you can produce on a site increases, owing to more skilled labour and better capital equipment. So what the site owner takes in rent gets far greater over time; the better the location, the greater the increase.

As he observed:

Take now… some hard-headed businessman, who has no theories, but knows how to make money. Say to him:

“Here is a little village; in ten years it will be a great city—in ten years the railroad will have taken the place of the stage coach, the electric light of the candle; it will abound with all the machinery and improvements that so enormously multiply the effective power of labour.”

“Will in ten years, interest be any higher?”

He will tell you, “No!”

“Will the wages of the common labourer be any higher…?”

He will tell you, “No the wages of common labour will not be any higher…”

“What, then, will be higher?”

“Rent, the value of land!” Go, get yourself a piece of ground, and hold possession!”

This is because land is fixed in quantity and immobile, while labour is neither. If wages rise in a particular occupation, there will be an increase in people who want to work there. The additional supply of people will bring wages back down. This happens also with returns to capital: excess profits are competed away.

This means that the residual – the surplus – can be charged by the landlord via rent or through the sales price for property. The immobility of land means that an increase in demand for sites cannot be met by a corresponding increase in supply. Because you have to be in a particular location to get the work done, this gives the landlord monopoly pricing power.

George made a critical point, however – he said that wages would not rise at all, or very little, in relative terms despite the major transition from a small village to a major city in the quote above.

I have alerted my readers to some research conducted by Don Riley, a landowner near London Bridge station. He had a first-hand view of the impact of the opening of the Jubilee Line on the value of his real estate portfolio in the 2000s. Through some careful observation and detailed research, he calculated the increase in the value of land around each station of the Jubilee Line extension. He published his findings in a book called Taken for a Ride.

His conclusion: shortly after the opening of the extension, property values had increased by £4 billion around each and every one of the new stations that opened up.

You can be sure that the wages of employees or profits of businesses around each station did not increase by anything like as much. If indeed they increased at all.

In the George model of the economy, we get recurring bouts of boom and bust because eventually as societies progress economically, rents grow much faster than wages or business profits. So more and more wealth is sucked into the pockets of landowners. For a time this is hidden because during an economic boom, you get extraordinary periods of wealth creation.

But eventually it gets to a point where businesses and households can take no more and have to cut back spending; this leads to a recession in economic growth, which causes land prices to come down hard leading to an economic depression.

The clear-out then resets the system for the next episode. I have shown you how this process takes a full 18 years to work through on average. (I described this process in detail in yesterday’s essay – check your inbox for more.)

The cycle arises because of the Law of Economic Rent in action. Because it still operates, you must get a real estate cycle.

We are presently close to the middle point of the present 18-year cycle, and I have forecast the peak of the cycle to arrive around 2026.

In the next section, I touch on why no expert can see it – because the very foundations of the economics have been corrupted.

“Why did no one see it coming?”

When HM The Queen visited the London School of Economics in November 2008 at the height of the global financial crisis, she posed the academics a very simple question along the lines of, “Why did no one see it coming?”

Addressing this seemingly simple question led to the convening of a British Academy Roundtable in 2009 involving more than 30 senior academics and senior public servants (including the cabinet secretary) that led to a published response. They talked about risks, the financial system and so on. But no one mentioned the main reason – how land, and land speculation, causes systemic financial crises.

Why were some of the most learned people country ignorant of the obvious answer – to do with speculation in the economic rent? This is an answer we have known about for over 140 years, from the time of Henry George, as I described above.

The only conclusion we can draw is that this ignorance is deliberate.

Yes, that right. We’re being deliberately kept in darkness. We are the victims of a cover-up on a grand scale. This means that anything you’ve ever read about economics investing or finance, is potentially suspect. And therefore knowledge of economic cycles will probably only ever be the preserve of a select group of people.

I will show you how and why this has come about and how the suppression of knowledge continues to this very day.

Silencing the most famous economist of all time

Earlier in this essay I mentioned Henry George and his study of economic rent and why the economy periodically has a major boom and then bust.

It’s likely that you had never heard of him, though. But if I were writing to you about 120 years ago, you certainly would have. When George published his findings about the boom and bust cycle in Progress and Poverty, in 1879 during the Long Depression, his ideas electrified the world.

In the closing decades of the 19th century, some estimate that Progress and Poverty outsold all other books, even the Bible. In fact, it sold so many copies during that period that it remains to this day, even a century of obscurity later, the most widely read economics book in history.

Progress and Poverty influenced such political and intellectual luminaries of the late 19th and 20th centuries as David Lloyd George, George Bernard Shaw, Sun Yat-sen, Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill and Leo Tolstoy (not to mention millions upon millions of ordinary citizens around the world).

When he passed away in 1897, George was given a statesman’s honours, with his coffin lying in state at Grand Central Station in New York City. More than 100,000 people came to pay their respects; it was the largest crowd of mourners to gather for any American figure since Abraham Lincoln’s funeral in 1865.

So how did such a famous and beloved public figure become so obscure?

The reason lies in George’s solution to the boom-bust cycle.

He argued that the economic rent of land was the best source of public taxation – because rents increased as the economy developed and so were publicly generated value. On the other hand, people’s incomes or business profits were privately generated value and should not be taken away by the taxman.

The key benefit of this was that taxation would boost economic activity because landowners would need to find people to use their land. And so this would set off a positive spiral of businesses having suitable places to locate their businesses to, competition for workers, rising wages, increasing demand and therefore increasing supply.

George was a pure free market economist. His proposals would have truly unshackled capitalism – as it was meant to be – and enable it to generate prosperity that was broad-based and widely shared. In addition, it would have been a version of capitalism where the greater your skill and effort, the more you are rewarded.

However, those who stood to lose out from his proposals – those who captured public value for their private benefit – were seriously worried at losing their ability to siphon off this value.

Their counter-attack was breath-taking.

The corruption of economics

So how was George’s ideas airbrushed from history? Economists Mason Gaffney and Fred Harrison detail the process clearly in their book The Corruption of Economics. If you have an economics background or an interest in the history of economic thought, this is a must-read work.

So persuasive were George’s arguments that several influential economists of the day set out on an amply funded plan to suppress the knowledge that landowners were “reaping what they did not sow.” What they needed was to show that rent-taking was useful in the same way that other incomes are the recompense that people and businesses take for the production of goods and services.

The device used was brilliant. Re-casting the classical economics tradition (the subject of Smith, Ricardo and Mill) as “neo-classical” (ie, implying a continuity with the past but updated to the present, industrial, age) their strategy was sublime in its simplicity. If you are unable to counter a strong argument whose logic is irrefutable, then the best strategy is to contaminate the terms of the debate until you are able to make your argument stick.

The three factors of production were replaced with just two – labour and capital. Land had disappeared from view, become a species of capital. When we talk about increases in the value of land today, it is termed “capital gains”.

Furthermore, the definition of capital was widened to include almost anything. Real capital – as understood by the classical economists – was defined precisely and consisted of things like machinery, factories, computers and the like; the things that we use to produce goods and services that an economy wants.

Think of it like this: real capital is what you would want were you marooned on a deserted island. The rest of what is regarded as capital, such as coins with a person’s head stamped on them, are not useful to you there.

Capital is man-made – it depreciates in value with wear and tear during production. When you want to expand production you need to increase your capital to do so.

At the same time, the new concept of capital had absorbed land. Land, however, is a separate factor of production. Land, unlike capital, is not man-made, it is supplied freely by nature and exists permanently. Land’s supply is fixed; capital’s supply can be increased with competition.

Taxes on capital reduce its supply and therefore suppress or distort economic activity. So taxing capital is an inherently bad thing for an economy. But this is not true of a tax, or service charge, on land. This merely reduces the price at which it would sell in a market place. But this price reflects its locational value – which is publicly generated. This means that the owner of a site cannot reap the benefits that he or she has not created (unearned income).

Therefore, conflating land with capital enables large landowners and their financiers to argue for lower taxes on capital – and therefore lower taxes on land.

Consequently, the economic rent from land becomes “income” rather than “unearned income” and our cities reflect Monopoly boards enriching the rentiers whilst impoverishing the tenants.

Our (economic) world is flat

The entire discipline in the 20th century was built on this foundation. Since there is no such thing as location in economic models, they are really reflecting a two-dimensional world. Their world is flat.

And out of this has grown the study of finance and investment theory which influences the decisions you make about your wealth – modern portfolio theory, capital asset pricing models, efficient market hypothesis and so on. Even newer strains of the subject – such as behavioural economics, which recognise the limits of human rationality and therefore the efficiency of markets – are modelled on a world where the underlying dynamics are not understood.

Open any economics textbook and look at the index. You will find little or no coverage of land but plenty about capital.

The intellectual sleight of hand was pretty subtle in the grand scheme of things. You may think this should only be of interest to hoary academics. But it’s hard to overstate how far-reaching its implications are. In the words of Gaffney and Harrison, those who attacked George had:

… emasculated the discipline, impoverished economic thought, muddled the minds of countless students, rationalized free-riding by landowners… rationalized chronic unemployment, hobbled us with today’s tax tangle… shattered our sense of community… and led us into becoming an increasingly nasty and dangerously divided plutocracy.

Though written in 1994, these words are highly relevant today.

If this story seems rather extreme for such a minor figure, then this is a measure of their success in suppressing George’s analysis. But the leader of this attack, J.B. Clark, was quite explicit in this intention as he made clear in the introductions of many of his works.

Ironically, as a young man, Clark had held progressive views; as a faculty member at Columbia University he became the mouthpiece of wealthy and corporate interests. In those days, there was no such thing as academic tenure and intellectual freedom and academics could be fired at will.

Columbia’s Department of Economics was bankrolled by J.P. Morgan. Elsewhere, the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School was quite blatant in its (negative) views of intellectual freedom, as explained by a trustee, Joseph Rosengarten:

… men holding teaching positions in the Wharton School introduce there doctrines wholly at variance with those of its founder… and talk wildly and in a manner entirely inconsistent with Mr Wharton’s well-known views and in defiance of the conservative opinions of men of affairs…

Mr Wharton’s views have not been handed down to us, but the large Wharton estate consisting of 100,000 acres in New Jersey, between Philadelphia and Atlantic City, might provide a clue as to what he would have thought of Henry George.

So this is the real reason why no one sees the cycle in action. Because the tools of the discipline are significantly limited.

But more power to us, I say.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this piece. Tomorrow, I am going to show how the idea of the economic rent can be applied in practice, and impacts how experts look at markets.

Best,

Akhil Patel

Guest editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates