Back when WuFlu was just a twinkle in some bat-eating deviant’s eye, I thought it’d be worth giving Seattle a visit. A reassuringly rainy area of the developed world with a strong beer culture and a view of the Pacific – seemed like it’d be worth a go.

The city has ended up becoming the Wuhan of the US however, and the Donald Trump administration banned UK citizens from entering the US two days before I could fly over and examine “Starbucks ground zero” with my own eyes.

Thing is, I’ve still got the fistful of dollars I intended to spend out there. While I may not be on holiday, these Benjamin Franklins certainly are, and now they’re in my possession I’m not sure when I’ll be exchanging them for Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth. For as fate would have it, I acquired them at an opportune time – right before there was a sudden demand for dollars within the financial system and ol’ Benjy began rising violently against other currencies.

Now of course, trading physical currency to make a profit is normally nigh-on impossible due to the high commissions charged in and out of by currency brokers. But based on the size of the move we’ve seen occur – and the size of the move that may be coming – I’m going to hold on to them.

But I’m not just writing to you about greenbacks because I happen to have bought some for a holiday that didn’t happen. The almighty dollar is important to all investors, and the UK is no exception. The FTSE 100 is full of global corporates with massive multinational operations – you think they invoice their business and mark up their accounts in sterling?

100 years ago that would’ve been the case, but these days megacorps like Unilever don’t keep score in sterling – they’re counting their profits in greenbacks. The same is true for our oil majors like BP and Shell, who sell oil for dollars despite being UK companies. Selling oil for sterling was one of the last pillars which held up the pound and the British Empire post-WWII – a dynamic the Americans deliberately destroyed in the decades after the war had ended.

The FTSE’s adoration of Benjamin Franklin means a weaker pound is good, as its profits are measured in dollars. That’s the FTSE 100 at least – the FTSE 250 is a more patriotic beast containing domestic-based companies that keep score of their profits in sterling. That’s why the pound’s crash after Brexit made the FTSE 100 rally, while the 250 floundered – the “tale of two FTSEs”.

But back to the task at hand. Despite the Federal Reserve sending hundreds of billions of dollars rocketing into the financial system, and making trillions of them available to banks in the US, the world is still short of dollars. We’ve written in recent letters how there’s been a flight to safety into the USD as it is the world’s reserve currency, and how margin calls and risky-asset selling has naturally made the currency stronger versus other assets.

But that’s looking mostly from within the financial system. The crash in the price of oil has compounded this, and with the Saudis saying they’re going to pump even more, the outlook is looking bleak for those bullish on black gold.

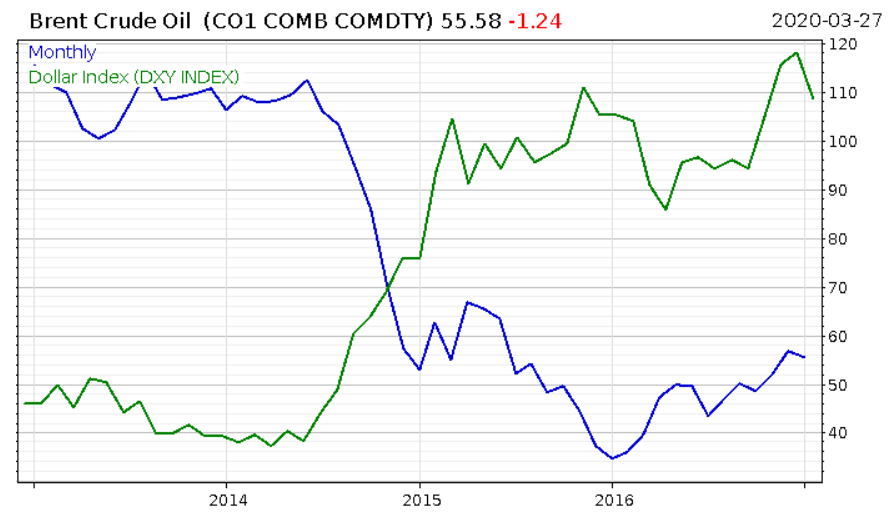

A low oil price creates dollar shortages because, quite simply, oil is priced in dollars. If a barrel of oil costs fewer dollars, then fewer dollars end up sloshing around in the areas where oil is pumped out of the ground.

You can see this dynamic illustrated quite plainly here – when the oil price (blue) crashed in 2014, oil producers around the world were earning less of them, and this contributed to the dollar shortage which made the dollar rally against other currencies (in green):

This same dynamic is playing out now, and that puts a lot of stress everywhere that dollars are needed – and that’s a lot of places. As emerging market countries have volatile currencies that few foreign investors are interested in holding on to (devaluation fears), they often borrow in dollars.

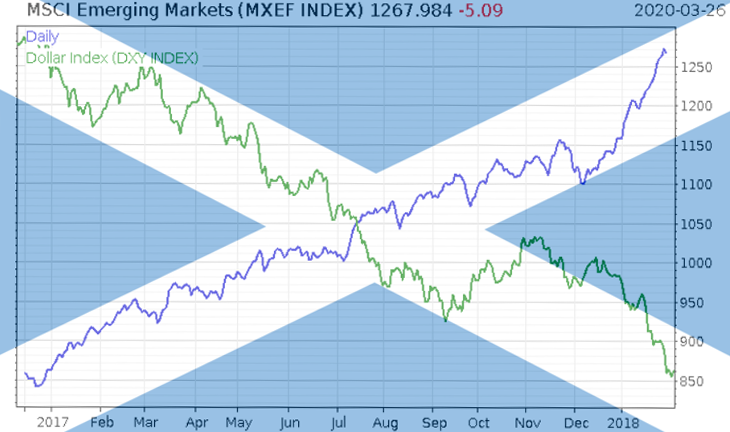

That’s why when the dollar weakens, emerging markets boom. This was perfectly demonstrated in 2017, with a chart pattern so clear it looks like a tribute to St Andrew. Emerging market stocks in blue, dollar in green:

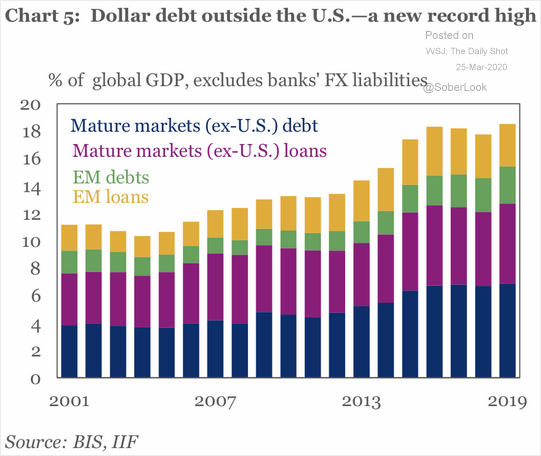

Major corporates also often borrow in dollars regardless of their nationality, simply because so much wealth is owned by dollar investors, and it’s them who want to lend it out. A large British company may want to borrow large sums of cash to finance its growth, but if there are no UK banks or investors interested, it may well look to the US market and borrow dollars instead.

Even Her Majesty’s Government has borrowed in dollars in the past. The market for offshore dollar loans is immense – and right now, there’s never been more of them out there.

Forget the political rhetoric about Trump – the dollar is hugely popular amongst foreign governments and companies:

Source: The Daily Shot, on Twitter

Source: The Daily Shot, on Twitter

John Connally, who served as the US Treasury secretary (and was in the car with JFK when he got shot), famously said the dollar was “Our currency, but your problem” to European finance ministers in the 70s. Richard Nixon had just gone off the gold standard, and the US no longer needed to spend within its means. The US government’s subsequent money printing devalued the holdings of all the foreign governments who held dollars, exporting inflation and igniting financial disruption within their economies.

The dollar is still the US’s currency, but the world’s problem – but this time around, it’s a deflationary force rather than an inflationary one (for the time being, at least).

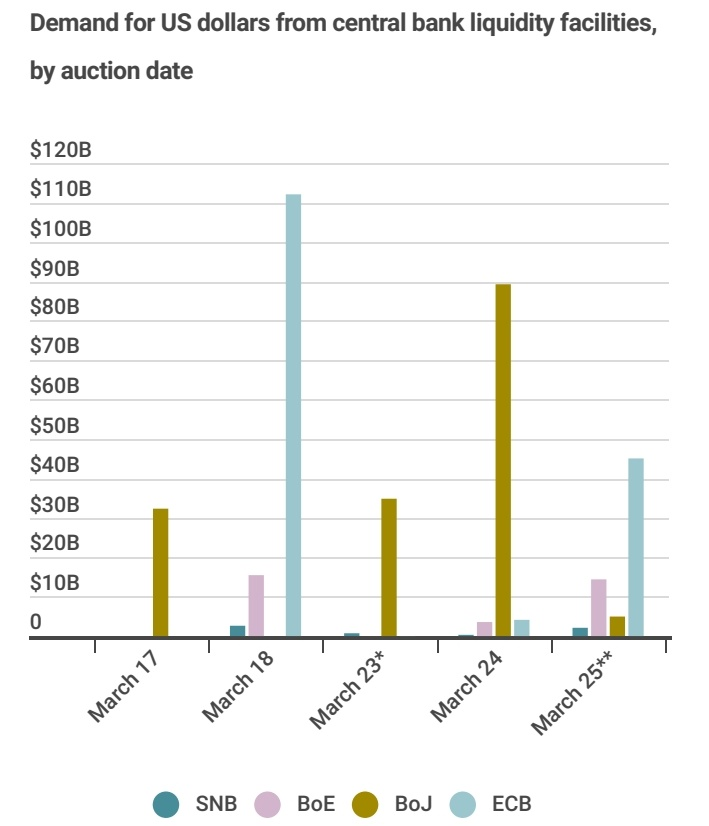

This time however, the Fed tries to help foreign governments out through something known as “swap lines”. For example: while the Bank of England can only print pounds, if it has a swap line with the Fed, it can borrow dollars from the Fed (“swapping” them for pounds, which the Fed in all likelihood does not need) and then lend them at low interest to banks suffering a dollar shortage in the UK.

Taking a look at who is using those swap lines gives you an idea of where in the developed world the dollar shortage is strongest. Thankfully, it’s not the Bank of England:

Yep, the eurozone and to a lesser extent, Japan, is desperate for those Benjamin Franklins. For all the political rhetoric about the euro becoming a global reserve currency and unseating the USD, the banks in the eurozone certainly doesn’t seem to have been listening to it…

This vast foreign dependence upon dollars reveals an economic reality which is likely considered politically incorrect, and few politicos will admit it. But the world is short of dollars, and it needs the Fed to keep them alive.

The question is, will swaps from the Fed provide enough dollars abroad to prevent the dollar shortage from crippling foreign banks, especially in Europe? And can the hyper-levered corporations who have borrowed so many dollars be able to survive a dollar famine?

For now, we’re watching the $DXY… and I’ll show you another index tomorrow that reveals how strong the stress is behind the scenes.

More to come…

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

For charts and other financial/geopolitical content, follow me on Twitter: @FederalExcess.

Category: Market updates