In these uncertain times it’s quite a claim to make that the biggest boom of all time is just around the corner.

But my study of market cycles leads me to this conclusion. The data is unambiguous.

How can I be so confident?

Well, we have the second half of the 18-year cycle to unfold in the 2020s. See Monday’s piece for a refresher on this cycle. The second half is the more bullish half when people are out making and spending money, borrowing and speculating in land.

There are signs that the cycle is now truly global.

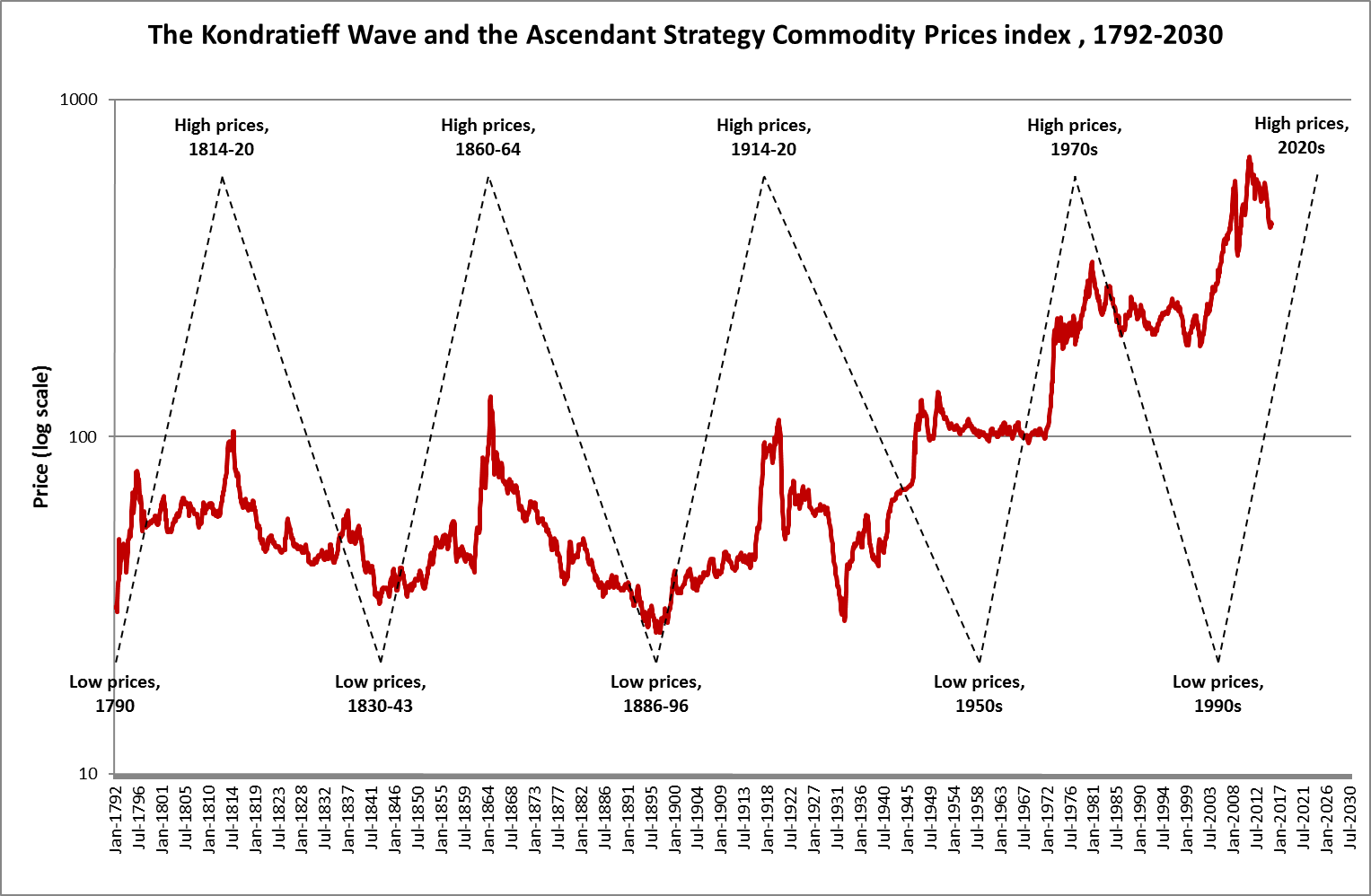

But there’s another cycle built into my bullish forecast: the Long Wave. This is also known as the Kondratiev Wave, after the Russian economist, Nikolai Kondratiev, who first identified it through his study of long-term commodity prices at the start of the 20th century.

The Long Wave of Progress

Kondratiev correctly identified, in long-term commodity price data, a rhythm of economic development that went in waves of approximately 50 to 60 years, 25 to 30 years up followed by 25 to 30 years down.

See the graphic below for my re-creation of his original analysis, extended to the present.

This price rhythm – which he called Long Waves – modulated periods of prosperity and recession in the economies he studied (principally Great Britain, France and the US).

Kondratiev’s brilliance was to observe in the historical data that each Long Wave would begin with an explosion of economic activity driven by the mass adoption of new technology, either through multiple technologies coming together in a cluster, finding new applications or costs of adoption falling dramatically (or all three).

The first Long Wave into a peak around 1815 saw the birth of the Industrial Revolution and the creation of the factory system of production. The second, into the late 1860s, was the age of the railroad. The third, into the 1920s, was the age of heavy industry and telecommunications. The fourth, into the 1970s, was the era of the motorcar, jet travel and the conquest of space.

These were highly disruptive periods where capital moved out of the old industries and supported the development of new industries. And on the back of this new deployment of scarce capital, whole new spheres of human activity were born.

Ultimately each Long Wave would see a complete re-ordering of industrial relations, modes of communication and transport and interactions between groups of people – particularly those in the older industries and those riding the wave of the new one.

These were highly bullish periods in human history, even if they were also quite turbulent because the old way of doing things was being challenged. But this disruption itself added fuel to the fire of prosperity.

It was the competition between the major economies of the day that drove innovation and therefore great leaps in general prosperity. An example is the space race during the Cold War, particularly during the late 1950s and 1960s. this great power rivalry between the US and USSR led to a whole host of technological developments that have widespread application today (MRI and CAT scanners, TV satellite dishes, smoke detectors, freeze-dried food, cordless tools, portable water filters and so on).

The biggest boom of all time is in front of us

I have said this before and will do so again: we are on the brink of the greatest wealth-building period in human history.

This is because we are approaching the peak of the Long Wave. The current upswing started in 2000 and should peak late 2020s. This is the age of the internet, new modes of manufacturing, biotech, and a host of other new technologies.

You only get the peaking of the real estate cycle and Long Waves at the same time once every 60 years. So these wealth-building opportunities are only likely to come around once in any investor’s life time.

And this time around, for the first time ever, the main centres of economic growth will not be concentrated in one region. There will be all spread all over the globe, led by the two largest economies (US and China). But all regions will participate in the boom to come, including South East Asia, Europe, Latin America and significant parts of Africa.

In 2016, Credit Suisse estimated global net household wealth at $256 trillion. This represents the stock of wealth owned by humanity across the globe. This means that this is the sum of whatever we have created to this point in our history.

But so bullish is the outlook that by 2026 I expect that this amount will have doubled – to around one half of one quadrillion dollars.

That’s $500,000,000,000,000.

We will double, within a decade, the amount of wealth that humanity has created from the dawn of civilisation to this point.

That’s how much wealth is going to be created.

The question is: are you in the frame of mind to make decisions that will enable you to take advantage?

Numbers this large are almost beyond comprehension. And if you think the world is on the brink of collapse under the weight of all its debts you’re not going to believe me. But it’s going to happen. Let me show you how.

The FTSE at 15,000 and the Dow Jones at 36,000

Given the fact that we are talking about both a property and natural resources boom, the FTSE should do very well given the listing of large natural resources, financial and house builders/construction companies in London.

In each of the prior cycles, the stockmarket in the second half of the cycle always goes higher than the peaks of the first half. How much higher might they go?

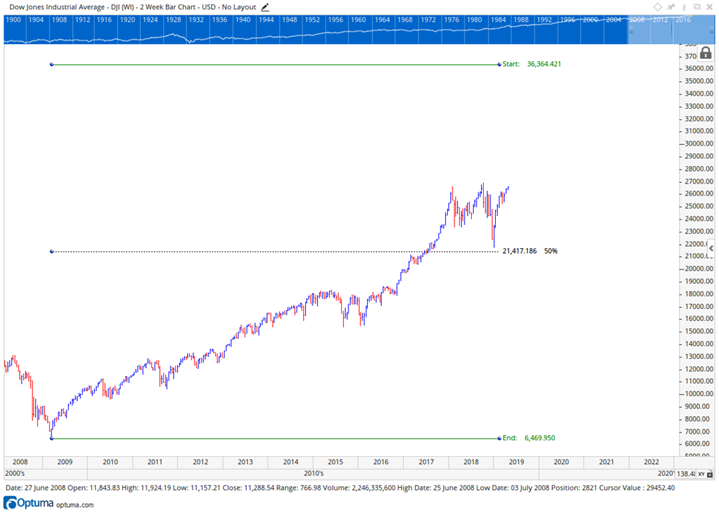

As ever, look at a chart.

A good way to judge how far a market could go is to look at key points of resistance on a chart and then look at multiples of that point once it breaks above them. Often these become new price targets of significance.

The FTSE 100 was constrained by the price level of 6,900-7,100 for many years, right from the time of the dotcom peak in 2000 to late 2016. It then broke out. The longer the period of resistance, according to legendary Wall Street trader W.D. Gann, the more important the breakout.

Such points of resistance end up being mid-points of the larger move. With nine years still ahead of us in this cycle, and the larger boom to come, it’s a reasonable forecast to make. It doesn’t take a great deal of imagination for you to see how the FTSE 100 could be at 14,000 to 15,000 in that period. A similar doubling of the Dow Jones Industrial Average from its 2016 breakout would see it above 36,000.

Competition for the control of the world

Amid the euphoria of a booming world economy during the next decade, there will be increasing evidence of competition between the great powers across a number of domains. Much will be in the technological space – around grabbing market share in sectors (automated transport, clean energy, high speed rail, biotech, robotics, fintech and the like). Investors and customers globally are going to benefit hugely from this intense competition.

But some of this conflict will be old-fashioned race to control territory and influence smaller nations. Currently, it is the US Navy in charge of the world’s main shipping routes and the US Air Force that is by far and away the strongest power in the skies.

China is keen to change the rules of the game. Control of territory means that you control trade. And in each previous Long Wave, there has always been tensions between the great powers of the day.

But while we may have concerns about how this great power competition will play out, it is important to note how bullish these are for markets and general prosperity.

China is making a big play across the Eurasian continent, looking to tie the entire region together into a major trading set of trading and transport networks, under what is now known as the Belt and Road Initiative (or BRI).

This has obvious economic benefits to China and its trading partners. One need not be overly cynical about Chinese motives. Much of their activity in relation to the BRI is a means of deploying excess domestic capacity. This is something China needs to do anyway, as it moves away from investment-led to a consumption-led growth model.

It has plenty of companies that can scale up construction and deploy labour abroad. In addition to this, megaprojects are tremendously lucrative for an economy, as well as for countries (like the UK) that provide associated services such as finance, legal and other professional services.

In another domain, there is increasing competition between the US and China. But this too is going to be lucrative for the rest of the world.

“Great powers have great currencies”

These were the words of Nobel Laureate, Robert Mundell. China knows this.

Currently the US dollar is almighty – the majority of the world’s reserves are held in dollars (over 60%) and more trade is settled in dollars (over 40%) than any other currency. It is a key plank on which American global hegemony is based.

This role gives the US a major advantage in global affairs, from reducing foreign exchange risk for many of its companies trading overseas to ensuring that there is an almost unquenchable appetite for dollars.

The latter in turns provides the US with profit (known as seigniorage, which is the difference between what a dollar can purchase in world markets and the cost of producing the dollar in the first place) and also ensures that it has access to all of the low-cost finance it needs, and so its companies can run deficits with abandon.

This system arose out of the Second World War and the Bretton Woods conference in 1944. That monetary agreement assigned to the US dollar the role of the world’s reserve currency and the only one fully convertible into gold (at $35 an ounce). Other currencies were pegged to the US dollar in a system of fixed exchange rates that supported reconstruction in Europe and prevented competitive devaluations.

These set of arrangements lasted until 1971 when currencies became freely floating. The US dollar was no longer convertible to gold at a fixed price once US President Richard Nixon closed the gold window. What is less well understood is that the US government swiftly instituted a system whereby the US dollar became convertible into oil – effectively giving rise to what some call the “petrodollar” system.

All of the major oil producers agreed (or were forced) to price their output in dollars in return for support for their regimes, non-interference by the US in their internal affairs and military defence. The main participants in this were, of course, Saudi Arabia and some OPEC members.

The dollar became the only currency in which energy could be bought and sold. This underpinned the dollar’s reserve status. This move was feasible because of the fact that the US dollar was so widely available at the time and because of the size of the US economy and its standing in the world (outside the communist system). This gave everyone reasonable access to dollars. Everyone needs oil, unlike gold which has virtually no intrinsic value other than the fact that we’re told it’s valuable and looks nice. To buy oil you need dollars. So all countries hold a lot of dollars.

But a rising China will challenge this.

Dollar dependence is not a big issue if you’re an ally of the US, as all Western nations are. The major issue is foreign exchange risk and the impact on bilateral trade this would have, when US goods become more or less expensive and US demand for your goods may fluctuate. Another issue is that these countries have to earn dollars through trade with the US (or with other countries who will then exchange currency for dollars).

On the other hand, those in competition or conflict with the US always have the prospect of US sanctions against them – as Iran and Russia can attest. The prevalence of the US dollar means that being frozen out of the dollar financial system can make purchasing energy and accessing finance from major banks difficult. This is because the banks will all have a level of participation in the dollar financial system and are therefore subject to punishment should they ignore the sanctions.

Understandably, the US’s rivals do not like the system.

As China assumes an ever greater role in the world economy – as its largest exporter and manufacturer – its own currency, the renminbi, will be used to settle more and more transactions.

And as the world’s largest importer and user of oil it would be keen to use its own currency to purchase energy, giving it the advantage that the US has had ever since the 1970s.

The petrodollar system is now under threat.

For example, both Saudi Arabia and Russia are vying for market share to supply China with the oil its growing economy needs. However, the Russians are willing to meet Chinese demands that payment is made in Chinese currency rather than dollars (unlike Saudi Arabia). And so Russia is in a more favourable position currently. Other oil producers may follow suit.

These actions would undermine the current system, which the US does so much to protect.

But will China’s renminbi be able to replace the dollar?

Could the renminbi supplant the dollar?

It’s possible but a number of things need to be in place first: widespread trade settlement in renminbi; liberalisation of the currency (allowing it to float freely and flow in and out of China); and its use as a reserve currency by other central banks.

China is working towards this but it is not a given as yet. But the implications are vast. For the Chinese currency to attain reserve status it would need to be widely available and for renminbi financial products to be developed for investors to purchase.

For example, bonds issued in RMB. And to do this, it needs global linkages and partners. And in the world of international finance, they don’t come much bigger than the City of London.

This also means lifting capital controls in China and allowing Chinese investors to push money abroad. Currently they are largely restricted from doing so. But the sums are vast. It is estimated that by 2030 China will have $17 trillion in funds under management (up from around $3 trillion currently). There has never been a period in human history where there has been such a rapid increase in capital looking for investment opportunities.

Even if only 30% of this left China, that could be a great wave of $5 trillion hitting assets all over the globe. This is a staggering economic opportunity particularly for those who already own good quality assets.

So even in this domain as well, great power rivalry will lead to many investment opportunities.

It means that the boom I have forecast for the next decade will be even bigger. As I say to my readers on a regular basis, it will be a great time to be an investor. You have to make sure you are positioned to take advantage.

Opportunities like this are not to be missed. I’ll be informing my subscribers where we are in the cycle as it unfolds, and how to ride the coming wealth boom to its fullest – if you’ve enjoyed this five-part series and want to learn more, .

Best,

Akhil Patel

Guest Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates