The last of the ancient horses’ asses (for this week, at least).

We began this series with a gem from Twitter, so it’s only fitting that we end with one too.

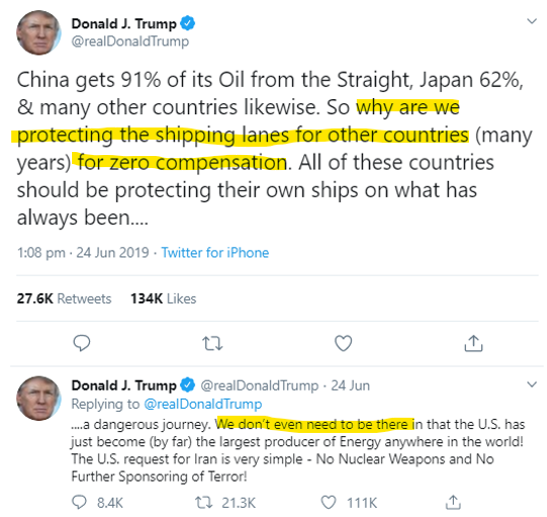

This one comes from none other than The Don himself back in June, referring to disturbances in the “Straight” of Hormuz (emphasis mine):

Like many things, The Don likes doing things his own way, and spelling is no exception

Like many things, The Don likes doing things his own way, and spelling is no exception

Source: Twitter

Yesterday we asked why oil tankers and container ships have evolved into lumbering behemoths as vulnerable as they are morbidly obese, despite carrying such precious cargo.

The answer is the US Navy, who turned the world’s shipping lanes into a “safe space”. Without risk of piracy or privateering by opposing nations, shipping companies and ports could gorge on cargo capacity, and achieve an economy of scale never seen before in history.

A reader wrote in yesterday who’d seen the beasts bred by a lack of risk up close:

[Last year I went to Nicaragua and] crossed the Atlantic by ship, not a cruise liner but a container ship which could carry upwards of 20,000 containers. A fascinating couple of weeks. As a passenger I was allowed to go anywhere on the ship although I had to be acccompanied in certain areas. The bridge was fascinating.

The engine room was absolutely huge, more like the inside of a cathedral than anything and this cathedral housed a 10 cylinder engine. Each cylinder could produce over 7,000 horse power and with all 10 at full power over 72,000 horse power was produced.

Then I found that the ship was not going along at full speed but only 80%. I asked the obvious question and was told that with the engine at 80% the ship consumed 147 tonnes of bunker fuel (the horrible stuff that is left over after everything else, such as diesel, kerosene and petrol has been distillated out. It has to be heated before it can be used it is so thick) per day if, however, the engine operated at full speed then the amount of fuel consumed would be nearly 250 tonnes per day…

They may not be able to escape adversaries or defend themselves, but those tankers sure can carry cargo in bulk. And as anyone who’s been to Costco will know, buying in bulk has benefits. The cost of transporting goods and oil overseas over the last several decades has been at bargain prices courtesy of the US, but nobody clocks that as the US Navy has been keeping the nursery cosy for so long.

But as The Don’s tweet reveals, the heating is going off, the door is being opened, and the winter chill is sweeping in.

The US’s safeguarding of the world’s shipping lanes are a key component of the US dollar’s global currency status. After all, if you have to use a fiat currency while invoicing and transacting large commercial sums abroad, you want a currency that is trustworthy and stable. And what better option than the currency of the Navy that’s out there maintaining stability for you out on the open seas for no reward?

This has a circular effect. Foreign companies using the dollar to conduct trade leads to dollars in the treasury of one company or another. And if they’ve got enough dollars, they’ll want to earn interest payments on them, so they’ll lend them to the US government (in the form of “investing in US Treasury bonds”), who then spends the cash on the US Navy.

And that Navy needs a lot of cash. To use a sporting analogy, imagine the large navies of the world are national teams. The Royal Navy, the Russian Navy, the French Navy, and the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) play games at home and away, against a few rivals.

The US Navy however, only plays away games (like Pakistan’s cricket team), and must be prepared to play every other team in every league on the same day. As a result, it’s a massive team, with a lot of substitutes (over 400,000 personnel), a hell of a lot of strategists, and a budget to match (over $150 billion a year).

If it were a country, the US Navy would have the world’s second largest air force, thanks to its 11 aircraft carriers. These pilots are entirely separate from the US Air Force (which is the largest, naturally), and aren’t trained anywhere near each other. The Navy is a silo of its own, with its own army – the Marine Corps – and its own Special Forces units, the SEALs.

There is no other navy on the planet even remotely close to rivalling the US’s ability to project power over the world’s oceans. A lot of that is courtesy of having as many aircraft carriers as the rest of the world combined, which are great for policing vast swathes of territory.

While China aims to rival the US at sea, and has developed missiles to ward the US off from its shores (a key “playing at home” advantage), it needs to boot the US from the South China Sea first before laying claim to the world’s oceans. Securing the world’s oceans and replacing Pax Americana with a Pax Sinica may well be its dream goal, but it’s a long way off in terms of the sheer capacity required.

(The Chinese government is pursuing a different strategy to get ahead of the US – like getting ahead in bleeding-edge technologies such as 5G applications, but we’ll focus on that next week.)

As the election of The Don and his tweets show, the US is no longer such a fan of the globalisation brought about by a “free and open maritime commons”. But no navy on the planet is prepared to take the US’s role in securing the world’s shipping lanes if it decided that it was time to hand in its world police badge. (And nor would that be anytime soon if that happened – navies are hugely expensive and take decades to build.)

Countries which can afford “blue water” navies of their own would no doubt try to secure and escort their own oil and shipping, but would leave massive gaps of unprotected territory, and those oil tankers and container ships would start looking mighty fat and slow. Maritime insurance would become very expensive, and naval private security firms would start to get a lot of business.

A higher cost of overseas transport for goods but more importantly for oil, is something very few investors expect, as everybody’s grown up with the world police patrolling the seas; it would blindside everybody with suddenly higher costs being injected into the base of the economy.

But there is one stay of the blade. The Don likes to make a deal, and with the amount of leverage the US has in this area, offers can be made which can’t be refused. As he noted in that tweet, why protect the world… for zero compensation?

In return for keeping the shipping lanes safe, they’ll want coin: literal “protection money”. A foreshadowing of this can be seen in South Korea where previously the US was happy to station its troops there with the South Koreans only chipping in $860 million. But the price has recently gone up… substantially. If the South Koreans want to keep US Marines drinking beer in Seoul, they’ll need to fork out $5 billion a year.

Going from the world’s greatest minder to its greatest mercenary may not be such a hard transition. The US would appear to be taking a leaf out of the British Empire’s book: transactionalism.

More to come next week – have a great weekend!

All the best,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates