Stocks went back to their falling ways once more overnight. It seems the occasional respite is just a so-called “dead cat bounce”.

The problem with a bear market now is that it begins with the FTSE index at the level it was at 18 years ago. Even if stocks are up since 2009, we haven’t had a proper bull market.

What about the alternatives? A 4% term deposit would’ve doubled your money over 18 years. The gold price is up about five-fold.

If I were you, I’d be utterly furious. What happened to “stocks go up in the long run”?

Not only that, but we’ve been at or around this level in the FTSE four times now! In 2000, 2007, 2015 and today.

Fifth time lucky?

FTSE 100 going nowhere

It gets even worse if you take a closer look at what’s actually in the index. Back in 2000, you would’ve owned specific stocks, not some index fund.

But less than half the companies from 18 years ago are even in the FTSE 100 any more! If you held the companies that disappeared, the actual returns on “buy and hold” are even worse than the index lets on. Your bank shares might’ve been acquired at the bottom in 2008, realising losses at the second worst possible time.

Throw in the benefits of dividends and the costs of inflation, my guess is you’re going nowhere. Over 18 years.

And now, just when stocks finally hit an all-time high, there’s a bear market on the cards. Stocks are tumbling.

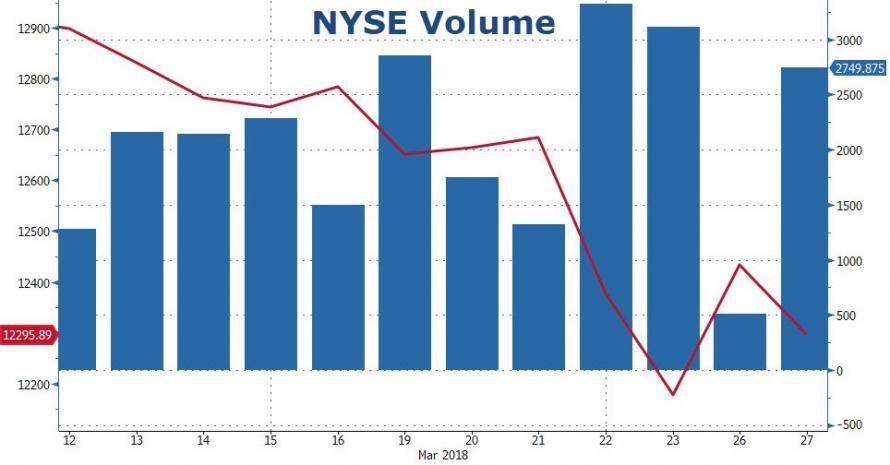

But what about the surge in stocks on Monday? Check out this chart from Zero Hedge. The blue bars are stockmarket volume, while the red line shows the index. The day stocks rallied, they did so on extremely low volume.

The idea is that the bounces in the stockmarket have no weight behind them. They’re big moves on low levels of actual buying and selling. Each time stocks recover, sellers use the jump as an opportunity to exit en masse.

But why are the selloffs happening in the first place?

There is a long list of potential answers. Perhaps all of them apply.

The trade war news coming out of Washington certainly seems to be determining the trend. Good news makes markets rally. Bad news and they fall.

The latest news was bad. Donald Trump intends to use emergency measures to implement trade barriers. Which sent markets tumbling back down. The day before, a compromise sent them up.

There are plenty of other concerns. The divergence between private borrowing rates and central bank rates, for example. The Libor-OIS spread continues to soar, which is why banks are among those hardest hit by the stockmarket turmoil so far. They’re supposed to outperform in interest rate upcycles.

The US economy is signalling trouble too. The US yield curve is tumbling towards recession predicting territory. By one measure, it’s at an 11-year low. That leads us back to 2007.

Let’s not get into causes today. Let’s ask about effects. What would a bear market of say 50% do to investors now?

Not that you aren’t used to it by now. It’s happened twice already. But I’m worried about the third time around.

The land of bear markets

If you tell a Japanese person you’re investing in property, they give you a funny look. Which is quite a dramatic affront coming from a Japanese person.

Pipe up about stocks and you’re considered a gambler. Young people are not interested at all. Just as one might “do drugs”, you can “do stocks”, as they put it in Japanese.

Japanese retail investors owned a record low of 17% of the Japanese stockmarket in 2016. And they were pulling money out on a net basis. Foreign investors owned 30% of the market and make up about 70% of trading volume.

It’s obvious why individuals don’t trust the stock or property market. Returns are miserable, even compared to the FTSE.

Commercial land prices rose over the last 12-month period for the first time in 26 years reported FT Alphaville. Until the recent global correction, the Nikkei 225 had reached a level not seen in 26 years too. It’s crossed the current level more than 20 times since the late 80s.

No wonder property investing is dumb and stocks are gambling. Long-term gains are non-existent. So much for stocks go up in the long run – the premise of investing in the West.

The cohort of Japanese who are supposed to be investing now are of course the ones least likely to invest. They saw what happened to their parents in the 90s. For some it was quite traumatic.

These days, the Bank of Japan and foreign traders are the biggest buyers of Japanese equities. Not exactly promising.

Instead of investing, the Japanese like to save money. While the world’s most avid stockmarket speculators like the US have remarkably low savings rates.

Compare these two quotes from Trading Economics:

“Household Saving Rate in Japan increased to 50.10 percent in December from 11.90 percent in November of 2017. Personal Savings in Japan averaged 11.94 percent from 1970 until 2017, reaching an all time high of 50.10 percent in December of 2017 […]”

“Household Saving Rate in the United States increased to 3.20 percent in January from 2.40 percent in December of 2017. Personal Savings in the United States averaged 8.26 percent from 1959 until 2018, reaching an all time high of 17 percent in May of 1975 and a record low of 1.90 percent in July of 2005.”

So many of those dates and figures are significant. The US savings rate peaked around about when the US economy did by many measures. And US savings rates fell alongside interest rates.

Japan has had pitiful returns for savers compared to the rest of the world, but savings rates seem to be rising.

Back to stocks, here’s my concern. What if another bear market turns the Western world Japanese? In other words, a prolonged bear market could ruin the promise and premise of investing. Instead, we’d all become savers to make up for the lack of returns. That would undermine the consumption economy. We’d experience a depression.

But if we’re set to follow Japan, as we already have on many counts, where is Japan going?

Is it a good place to invest? As of yesterday, it looks like I’ll have about six months to figure it out. I’ll be moving to Komatsu, the birthplace of the Komatsu excavators you might see on building sites in the UK.

次回まで,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Tim was RIGHT

Related Articles:

- Trump schools May in trade agreements

- The Dear Leader and the stockmarket

- Mistreatment after a misdiagnosis

Category: Economics