The UK property market has peaked, and 18 years of decline lie ahead. So says one of America’s most unorthodox forecasters.

London specifically, he says, is “starting to appear like an abyss”.

Today, we look at Martin Armstrong’s real estate cycle. And we ask, “is he right?”

Martin Armstrong – fact is stranger than fiction

If you wrote a thriller based on Martin Armstrong’s life, it would probably be deemed ‘too unbelievable’.

His father lost all his money in the 1929 crash. Armstrong, on the other hand, was a millionaire by the time he was 15. He took to forecasting as a hobby, and his model led him to be a vastly successful investment manager. He is said to have predicted the 1987 crash to the day, as well as the subsequent low, the Nikkei top, Russia’s debt default, and the Long-Term Capital Management crisis.

But millions of dollars of Japanese funds went missing in the 1990s. He was indicted and told to hand over his computers, as well as gold and coins. Accusations abounded that the arrest was just the CIA trying to get hold of his super-computer with “perhaps the largest economic database in the world”.

Armstrong complied, but failed to hand over all of the assets requested, saying he didn’t have them. As a result, from 2000, he was held in prison – without trial – for a record seven years for contempt of court. He eventually pleaded guilty to a single charge (conspiracy to commit securities fraud) and was eventually released in 2011 – and he went straight back in the forecasting business.

I’m cynical about cycles – but there’s something to this

Armstrong’s Economic Confidence Model, which enabled him to make these uncannily accurate predictions, was based on economic cycles he had identified looking back at hundreds of years of data.

There was a long-term business cycle of 309.6 years, which is broken down into six waves of 51.6 years (the same duration as Russian economist Nikolai Kondratiev’s famous cycle). Armstrong then broke this wave down into six waves of 8.6 years each.

The total number of days in one 8.6 year cycle is 3,141 – pi times 1,000. Hence the model is also known as the ‘Pi Cycle’.

I have to say, I’ve grown very cynical about cycle forecasters over the years. It’s too easy to look at past events, find a pattern of some kind and declare you have a cycle.

A lot of Kondratiev stuff did the rounds a few years ago. Events just didn’t pan out in the way proponents said they would. We never got the fall of Rome, the economic winter or any of that stuff. It just didn’t happen. The retort came that government intervention had prolonged a certain part of the cycle. Well, maybe – whatever. The bottom line is that the cycle didn’t work.

The same goes for Fred Harrison’s 18-year property cycle that was popular for a while. The crash that came in 2008 (in my areas at least) was so marginal as to be untradeable.

The commodity supercycle was supposed to go on for 20 years. It only lasted ten. The four-year cycle in US stocks is only ever perceived after the event.

So I’ve always found cycles rather more academic than practical.

But, I have to say, I do find the argument behind Armstrong’s property cycle persuasive. The thrust is not price-to-earnings ratios, excess debt, a surfeit of supply or any of the traditional value arguments towards property. It’s government intervention.

“What will make the peak is a rise in taxes”, he says. Governments are bankrupt and so will make “insane increases in taxes as they try to stay afloat”. In addition, he says, there is a lack of long-term mortgage availability – lack of credit in other words. And over the past fortnight he’s been aggressively calling the top in real estate – here, in the US, and elsewhere. He’s even sold his mother’s house.

Is the UK’s attitude to property changing?

Here in the UK, government policies have conspired to drive up or prop up property prices since before I can remember. A crazy system of credit; a failure to include property prices in official inflation measures; suppression of interest rates to keep borrowing costs down; restrictive planning laws; and so on.

But that might slowly be changing.

Whereas once upon a time every government strategy was about propping up and boosting prices, now the demographics are changing. The non-owning young are on the increase. According to one paper I read they will be in the majority by 2022. Property is no longer such a sacred cow.

At the top-end of the market we’ve already seen the attack on non-doms, and higher stamp duty on expensive real estate. In the latest budget we got the first, possibly of many, salvos into buy-to-let with the change to exemption of borrowing costs. The Mortgage Market Review and the death of self-cert have made mortgages harder to obtain.

But there’s a lot more potential squeezing of this little piggy to come. For all the misinformation being perpetrated by George Osborne and the Treasury about getting the UK’s finances in shape, government is still spending way more than it earns. One of the few places it can tax where it doesn’t already is real estate.

Unoccupied property is something I have brought up before. It’s a growing issue, particularly in London. We may see a tax on that. The re-rating of council tax bands so that rates go up for more expensive properties is, I would say, just matter of time.

Before the election, my colleague Merryn made the argument that, such is the shape of government finance, a mansion tax is inevitable whoever wins (the Tories just won’t call it that).

Many are calling for capital gains taxes to be levied on the main home. And now that the floodgates have been opened, further tax forays into buy-to-let look likely. The idea of a land-value tax is gaining traction.

In terms of transaction levels, intervention has already crashed this market. Volumes have capitulated. The costs of moving – in terms of tax, lost mortgage deals, tighter lending – already means many are choosing to stay put. The question is whether price will follow volume – it doesn’t always.

Armstrong thinks it will – prices come into line with cash available for deals, Armstrong says. But In London, it should be stressed, with cash buyers on the rise, and lending tighter, that is already happening – and it hasn’t driven down prices so far.

So are we heading for an 18-year slump?

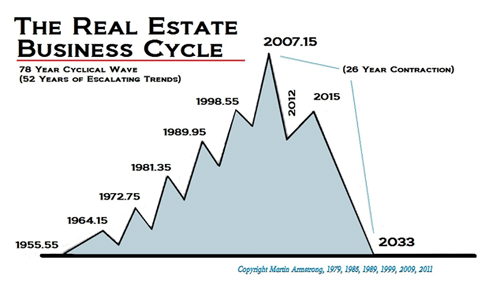

Here is Armstrong’s 78-year cycle. We see 52 years rising, from 1955 to 2007, and then 26 years of decline.

The stated dates mark turning points.

To explain his date system – 2007.15 equates to 0.15 the way through 2007. There are 365 days in the year – 365×0.15 = 54.75. The 54th day of the year is 27 February – so that was the turn date.

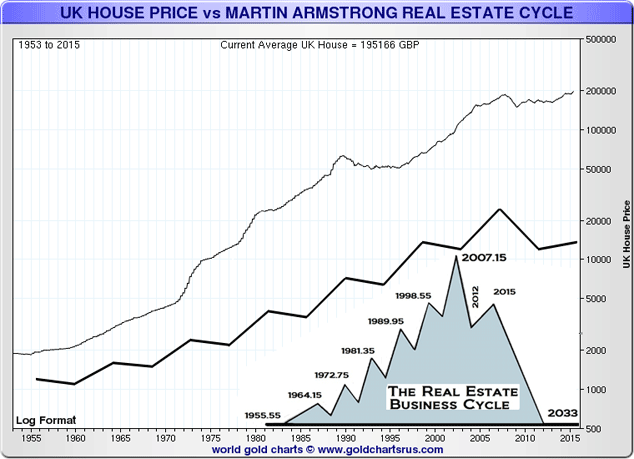

I took Armstrong’s real estate cycle, sent it to my chart wrangler, Nick Laird of Sharelynx, and asked him to transpose it onto a long-term chart of UK property.

And there is some correlation.

The thin black line in the chart below is UK property since 1955. The zig-zaggy line is Armstrong’s cycle.

The cycle is by no means perfect. But 2012 did kind of mark the point at which London started to go bananas. His 2007 high coincided with the top in UK property.

1998 was a take-off point. 1989 was a high (before the bear market of 1989-94). 1981 was a take-off point, and so on.

I guess we’ll have a pretty good idea within six months or so whether the declines he sees ahead is actually starting to materialise. It does seem to me that, while parts of the UK are rising slightly, most of it is stagnant, particularly London.

I’m very bearish about London new-build as I’ve said before – particularly in SW8 – and would short it if I could. Most of it is ugly and characterless, not what Londoners want, particularly at that price. About period property, I’m ambivalent.

My own experience as 45 years a Londoner tells me never to bet against London property. But maybe that’s because my life has coincided with an escalating trend.

• Dominic Frisby is the author of Life After The State and Bitcoin: the Future of Money.

Category: Economics