It doesn’t matter who you are, debt will solve your problem.

If you’re a company CEO whose job and pay packet are all about raising the share price, the answer to your challenge is simple – debt. You just need to borrow money and buy your own company’s shares. The price will rise and you’ll be a genius. A rich one too.

The New York Post explains this isn’t exactly a farfetched theory. It’s standard practice on Wall Street:

It’s the “shock” market rally — cash-rich US companies have plunged nearly $4 trillion of their cash into buying back their stock since 2008, which is why all the stock indexes are hovering near record territory.

“It has massively manipulated the market,” said Richard Bowen, the former Citi executive who blew the whistle on the bank during the subprime mortgage crisis, and noted how these share buybacks in the open market were once deemed illegal. The Securities and Exchange Commission eased the rules in the early ’80s.

“This market scares the crap out of me,” Bowen, sensing a potential financial disaster, told The Post.

The figures mean companies are the biggest buyers of their own shares over the last decade. Last year, 66% of earnings went to buybacks.

But it’s the huge amount of leverage that’s the real worry. Companies are borrowing to buy their own shares. The figures are tough to untangle, but Yahoo Finance estimated 39% of buybacks in the US were funded by debt in 2016. The previous peak in the trend was in early 2008.

Leveraged buybacks increase debt and make the leverage ratio rise thanks to less equity at the same time. It’s double the effect.

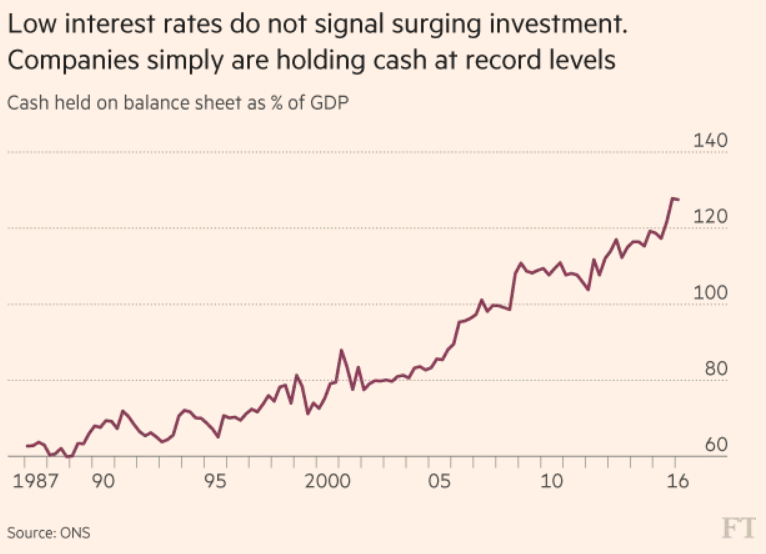

In the UK, the buyback activity has been less, but still present. The government even announced an enquiry into the practice last year. But it seems companies in the UK are mostly just sitting on huge piles of cash they’ve borrowed:

The reasons for doing so are simple. Record low interest rates incentivised borrowing. But a poor economic recovery didn’t encourage investing. To make stock prices rise anyway, companies just bought their own shares. And executives collected impressive bonuses for this incredibly useful economic activity…

What about consumers? Debt can solve their problems too. If you can’t afford something, it hardly matters these days. Just borrow the money.

Consumer credit peaked at 45% of UK household income in 2007. It crashed to a low of 35% in 2012, but will surpass the previous peak by 2021 according to the Office for Budget Responsibility. Annual car debt issuance and student debt have doubled in five years

Homeowners are the biggest part of the “debt solves everything” story. With your ability to own a home determined by your willingness to go into debt, the threshold is being pushed over time.

The government’s solution to the mortgage debt problem was simple. Encourage people to borrow more money they can’t afford by helping them with their deposit. This of course only transfers debt to the government. And pushes house prices up more, requiring even more debt to buy them.

Another concerning trend is interest only mortgages. Borrowers have given up on the idea of actually repaying their mortgage. These days, one in five are interest only according to the Financial Conduct Authority.

The extent of UK household debt is so bad that an executive director of the Financial Conduct Authority had to say this about his crackdown:

“A business model that is predicated on selling products to customers who can’t afford to repay them is not acceptable.

“We will take action against firms who run their businesses this way.”

Lending to people who can’t afford to repay… what sort of a business model is that? Er, wait, it’s government policy under the Help to Buy scheme…

Put all this UK household debt together and you have the second most indebted consumers in the G8. Britain’s households are very vulnerable.

But the biggest borrowers are governments. Debt accountability is lowest for them. After all, the time during which politicians are actually responsible for the debt is limited. The chances of anything going wrong in those glorious years are slim. And you can blame your predecessors for the debt build-up of the past.

The results of this system are all over the news. Governments promise all sorts of wacky policies. And just borrow to pay for them. How any government can lose an election with that sort of financial backing is a mystery.

For some strange reason we compare government debt as a proportion of GDP. Everyone else’s debt is compared to their income. But governments’ have theirs compared to the whole nation’s GDP. This makes no sense to me.

The average UK mortgage balance is about £120,000. So our average debt to GDP for mortgaged households is 0.00006%. A meaningless number, because none of us have a claim on the country’s GDP to pay off our debt.

But neither does the government. It only has a claim on tax revenue – about £680 billion. So why do we look at the government’s debt to GDP instead of its tax revenue? The governments’ revenue is a share of GDP, just as your income is a share of GDP. About a third, in the government’s case.

Homeowners have their actual income compared to their debts, so what is the government’s equivalent figure? With £680 billion in tax revenue and close to £2 trillion in debt, our government debt is three times tax revenue. Compared to a mortgage borrower, that’s within the rule of thumb – you can borrow 3-5 times your income.

The government only spends about 8% of its tax revenue on servicing its debt though. UK borrowers can expect to spend about a third. The key difference is that the UK runs on a type of interest only mortgage. It just repays old debt with new, a never-ending refinancing loan.

That’s the state of things in our world of debt. The question is, what does it mean? And where does it leave us?

Does debt matter anymore?

Perhaps the strangest part of our debt-based world is how we equate borrowing with economic prosperity. Commentators say borrowing shows optimism about the future.

But on the street, it’s actually just a matter of survival and providing shelter for many people. They’d pay their bills with earnings and savings if they could.

What baffles me most of all is that the true nature of debt isn’t even considered in this view that borrowing is good. Getting into debt is a sacrifice of future income in favour of the present. It is inherently bad for the future. Unless you spend your money on something productive.

The companies borrowing money to buy their own shares are the obvious example. This borrowing is unproductive. When interest rates rise or a recession comes, they’ll struggle to repay their debts.

The solution will be to issue the shares they had bought, diluting shareholders and crushing returns at the worst possible time. Cue a stockmarket plunge.

But perhaps I’m just a little fuddy duddy about all this. Are we in a new age, where debt doesn’t matter? Or is a reckoning coming?

If governments and companies don’t have to repay debt anymore, they only have to roll over that debt by repaying maturing bonds with money from newly issue bonds, then why can’t consumers do the same thing? They’re already using interest-only mortgages.

It’s also a valid question to ask where we’d be without all this debt. How many fewer cars would we own? What would our homes look like and how many would there be? Could we buy iPhones?

Years ago I discovered an economist whose name I can’t recall. He or she pointed out that, for all its contradictions and imbalances, the debt-based economic system worked wonders for our living standards.

If the debt system implodes, we’ll still be left with a huge chunk of its benefits. The cars, houses and technology created by debt would still be there after the debt-based system disappears.

What about the lenders? They’re practically just accounting constructs anyway, creating money and debt out of thin air.

In the midst of this debt bloom, you also have to wonder what role interest rates and monetary policy play. Are they used to manage the economy? Or are they a panicky reaction to the amount of debt in the economy?

What if central bankers have lost control of borrowers? What if we now see the purpose of the Bank of England as an enabler of debt by lowering interest rates when we max out? And the regulatory bodies are there to rescue us with borrower friendly laws too.

We rely on the rescue efforts of our institutions to help us with too much debt. Which allows us to borrow even more.

Above, we looked into the liability side of this debt-based system. But what’s even more scary is the extent to which debt is also on the asset side of our lives.

About three times more bonds trade each day than shares. The global bond market is about 50% larger than the global stockmarket.

However indirectly, people own these bonds. They depend on them for their pension and retirement. If the debts cannot be repaid, what will pay our pension income?

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates