If you woke up with your ears ringing on Friday morning by now you’ll know why. In overnight trading – when only the Asian markets were open and liquidity was low – the pound crashed at such speed it almost broke the sound barrier with a sonic boom.

Of course, most markets don’t operate an open outcry, ie, people actually communicating (and shouting) with each other on the trading floor, any longer. The “sound” of a market is generally the hum of machines talking to one another and executing trades.

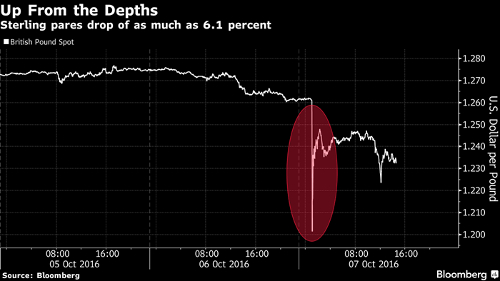

Which is pertinent to us today. Friday’s crash in the pound was a “flash crash”. It plunged more than 6% in less than two minutes, hitting $1.13 on the dollar at one point before recovering to $1.24. Think of it like a plane suddenly losing altitude, before correcting itself. All in the space of a couple of minutes.

Not good for the stomach. Or the mind. The question is, why did it happen?

Why the pound went boom

The simple answer is that markets are largely automated. Vast volumes of trades are executed by high frequency traders (HFTs) – algorithms that can perform large numbers of trades each minute on autopilot.

Automation is supposed to bring greater efficiency – with so many HFTs in the market, there’s more liquidity around and it’s more likely you’ll be able to get into or out of a position quickly, because there’ll always be someone, or something, willing to take the other side of the trade.

But the price of automation is that it largely removes human judgement. Pesky old humans slow things down. An algorithm doesn’t need someone to weigh whether an asset is a buy or a sell. It figures it out for itself in less than the time it took you to read this sentence. Most of the time that’s ok. Very occasionally it’s not. Sometimes there’s a glitch in the system and large numbers of HTFs start selling at the same time. The bottom drops out of the market and you get a flash crash, like this:

That’s the consensus view of what happened to the pound: a flash crash, as we’ve seen in numerous other markets in the last five years (there have been flash crashes in the South African rand and New Zealand dollar this year already). As Bloomberg reported portfolio manager Ryan Myerberg saying, “We’ll probably never know why it has actually sold off, if it’s a fat finger, or just algos. There’s no doubt that there’s an electronic component to it.”

To me that sounds like even the people operating in a market don’t really understand its structure, or how the algorithms within it, actually work. That’s a story for another day. For now let’s keep our eyes on the pound and try to figure out what happened.

Because had this happened to another currency, even a big one like the yen or euro, perhaps we could simply blame the algorithms and move on. But the pound is the chokepoint of so many key economic and political trends at the moment that we can’t do that here.

Besides, the “algos” were just the mechanism for the crash. The pound was on the slide all week. There are other forces at work here.

And those forces aren’t automated. They are entirely a matter of human judgment: the people of Britain judged it best to leave the EU, Theresa May’s government now has to judge the best way of bringing that about, and the market has to judge what those plans will mean for Britain and the world.

That’s proving hard. Markets aren’t perfect. But they’re the best method we know of for figuring out the price of things. Working out what a pound is worth at a time when so much is undecided – when there’s so little concrete information on which to base your decision – creates volatility.

Or perhaps this isn’t just volatility. Maybe an unstable, falling currency is the price you pay for taking back political decision-making power and making it clear you’d like to manage your own border control. That may well be fine. The economy seems to be chugging along ok and the stock market is a breath away from all-time highs. We’re not seeing asset prices collapse across the board.

Maybe the pound is where we pay the natural market price of Brexit. If so, is it worth it?

A conspiracy against sterling

Or perhaps it is something more sinister.

There are plenty of people out there who’d love Brexit to fail, or who’d like to make it clear to the government that whatever their policy is it’ll have consequences. Last week it looked like the government may pursue a “hard Brexit”, which seems to mean no access to the single market in exchange for limits on the movement of people. Theresa May has also suggested that the City won’t get a special deal designed to protect its status as a financial hub.

We know prices are signals. But maybe the price action in the pound was a signal intended for just one person: Theresa May. A message from the EU and the banks that her current course will have consequences.

As Francoise Hollande said just hours before the pound collapsed: “There must be a threat, there must be a risk, there must be a price, otherwise we will be in negotiations that will not end well and, inevitably, will have economic and human consequences.” (Emphasis is mine.)

I’m sure Hollande was talking generally. I’d like to think that no politician or political organisation is powerful enough to crash a global currency. But what I’d like to think and what’s true are two different things.

Ultimately it doesn’t really matter whether someone purposefully caused a crash like this to happen to send a message to the government or not. But if I was a lobbyist for the banking industry trying to get a better deal from the government, or an EU negotiator preparing for battle to commence next year, I know that the events of Friday morning would strengthen my hand.

SDRs, gold and the rewriting of the monetary rulebook

Or has everyone got the story wrong. We’ve spoken about automation and political judgment. Maybe this is something different. Whilst Britain focuses on Brexit, the rules of the global monetary system are being rewritten – and not necessarily in our favour.

I’m talking about Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). An SDR is essentially an IMF currency, but one only central banks can hold reserves of. You couldn’t buy a pint with an SDR, but somewhere deep in the system SDRs play a role in the way central banks manage their currencies, including the pound.

The value of an SDR is based on a basket of currencies stipulated by the IMF. In that sense it’s like a central bankers reserve currency. And here’s the thing: less than two weeks ago, the IMF reduced the pound’s weighting in that basket. Within days of that happening the pound hit a 31-year low against the dollar and experienced a flash crash. Coincidence?

Category: Economics